All the King's Men Part I: There ain't enough bods

A Quickfire on workforce woes in the modern British Military

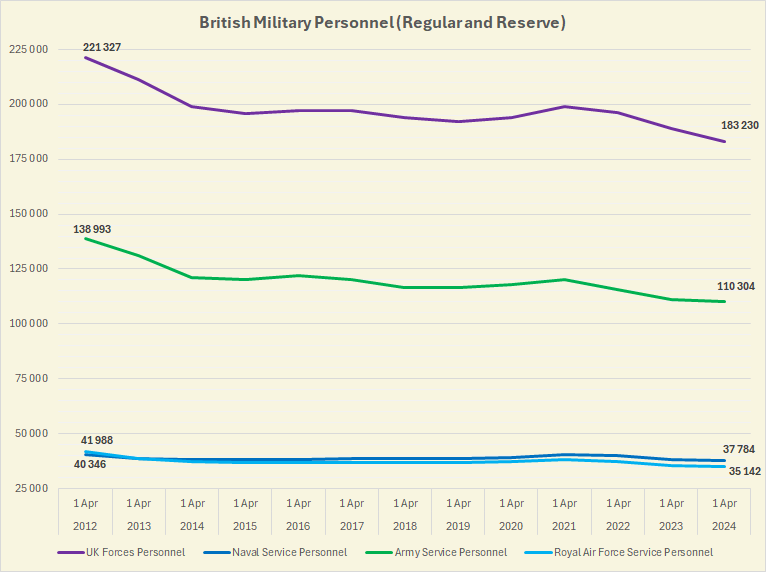

Every article about British defence personnel today is obligated to inform you that the British Army is smaller today than it has been at any point since the Napoleonic Wars. The validity of this comparison is questionable; what is not is that the Forces are lacking personnel across the board, and people are leaving the service at a faster rate than they can be replaced.

As such, the Armed Forces struggle to meet the outputs required of it by government. There aren’t enough troops to man the garrisons, pilots to fly planes and preen, matelots to sail about and staff officers to shuffle powerpoint slides around. Talk to any military person and you will hear constant stories of people getting ripped out of their official job and getting trawled for higher-priority roles. The MOD is busy, continues to get busier, and can’t keep critical outputs staffed without severely deprioritising others.

It highly unlikely that the outputs demanded of the MOD are going to significantly decrease: the world is too dangerous, crises appear out of nowhere on a regular basis, and the political and strategic risks of significantly cutting back on standing commitments is extremely high. Therefore, we are going to need more people to meet the challenges of today, let alone during a potential conventional war. It is arguably a far more urgent issue to fix than the MOD’s many other woes - frankly, there is no point in having a fancy fleet of uber-tanks if there is nobody to operate them.

To start, the net bleed of personnel out of the forces needs to be stemmed. Poor retention is an issue suffered by militaries across the developed world, and the British Armed Forces are no exception. A few points should be borne in mind. Firstly (and obviously) improve conditions: (far) better quality accommodation, offices, food, and higher pay, especially for those with niche technical skills who can walk into civilian jobs earning 2-3x their military salary. Next is to update the terms of service and archaic career structure, including more ability to move around and outside the Forces without sacrificing career progression. The needs of spouses and families need to be seriously considered as well; it is currently difficult for partners to both live together and hold up sustained careers due to the itinerant and geographically isolated nature of much military life: the old standard of ‘wife gives up career and follows husband around’ does not really cut it anymore.

The second is to increase input of recruits and reduce friction to entry, most notably by making the infamously slow recruitment system speedier and less torturous (ideally by binning Capita sooner rather than later). Easing up ludicrously-high medical entry standards would also help, as plenty of good recruits are rejected for the most miniscule of childhood medical conditions. Finally, the Armed Forces need to reach out to women more; only 12% of military personnel are female, compared to 51% of the overall British population, suggesting a vast untapped pool of potential recruits. Curbing the still-rampant sexism present in the Armed Forces would be a start to encouraging women to join the military in greater numbers.

Much of the above is being attempted by the MOD, but arguably not fast enough – though the news this week of a 6% pay rise is welcome. Contracting and Reservist mobilisation can temporarily fill some of the gaps, but the first is expensive and the second, as I will write about in the third part of this little series, is hampered by Reservists leaving service at a greater rate than regulars. We are likely to see continued net outflow for some time until the overall package of remuneration, lifestyle, and career is improved.

The dearth of people leads to acute structural brittleness. In case of a balloon-goes-up, oh-Christ-here-we-go full scale war, large gaps are going to appear very quickly due to casualties, and that brittleness is going to be tested to destruction.

In Part II, I’ll look at the issue of mass in wartime.

The same is for a large part true and applicable to the Netherlands Armed Forces. (Also because we too have a King and Royal Army/Navy/etc ;) )

In the Netherlands we are seeing some good initiatives like a ‘year of service’ in order to attract young people quickly and only for a short time, hoping that many of them will stick around for longer term contracts. This only solves part of the recruitment of soldiers, sailors and the like. This solution does not solve many of the other problems you mention, like the archaic career system for NCO’s and officers.

When a war will break out in Europe, we will need more drastic measures like a reactivation of the draft, or something equivalent. There is too little political support for that now in the Netherlands though, and expect in more NATO allies. In my opinion, the best insurance now is to enlarge the number of reservists. Countries like Finland (that have conscription) can call upon large numbers of troops in case of emergencies. This way, you have an insurance policy and continued participation in the economy.

With regards to recruitment - I see army recruitment ads quite often, both on TV and online. Must be costing a fortune without seemingly bearing much fruit.