Manoeuvre Warfare is a Social Construct

Or, we all want to be Napoleon

This is not, really, an article about military theory. Instead, it is about how armed forces view military theory and are shaped by their conceptions.

Militaries design themselves based on how they expect to fight in future wars, and – just as importantly – on how they conceptualise themselves and their likely enemies. Many NATO militaries have a particular reverence for warfare based on ‘manoeuvre’, which at times is imbued with almost mystical reverence, and a corresponding disdain for warfare based on ‘attrition’ or ‘position’. This is a social construction by western militaries and has real implications for policy decisions made about national defence.

A Brief Intro: Manoeuvre, Attrition, and Position

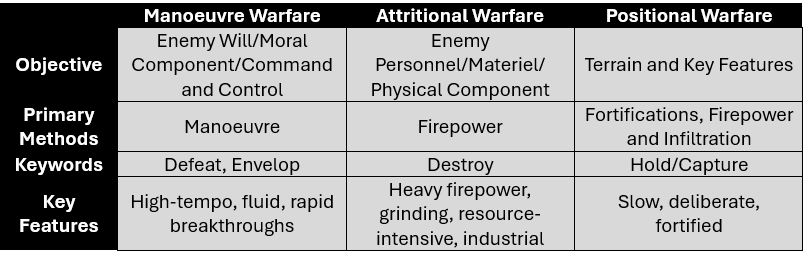

Bear with me for this – lots of dull theoretical terms, but I promise it will get more interesting! To start: Behold, a simplified and abridged guide to three contested terms and ‘forms of warfare’ in military science:

Manoeuvre Warfare: Manoeuvre is generally defined as: ‘Movement and employment of force to achieve a position of relative advantage over the enemy’. Warfare or tactics based on manoeuvre are generally seen as high-tempo, fast, and aimed primarily at defeating the enemy through breaking his will to fight rather than necessarily destroying all his forces or capturing his territory.

One example might be a military unit managing to get on the flank of an enemy, therefore putting themselves in an advantageous position. Another might be deceiving an enemy to allow for an attack on rear positions, crippling supply lines. Manoeuvre does not have to necessarily involve physical movement (you can have ‘electromagnetic’ or ‘information’ manoeuvre, for example) but in most cases it does and physical manoeuvre is the easiest to conceptualise.

Classic Historic Example: Napoleon’s envelopment of the Austrian army during the Ulm campaign, leading the defeat and surrender of General Mack (‘the unfortunate Mack’) in a matter of days with minimal French casualties.

Attritional Warfare: Attrition is perhaps best defined as ‘the sustained process of wearing down an opponent’. Attrition happens when you lose equipment and people to the extent that it impacts your ability to operate as a military unit. In a wartime scenario, this usually happens most rapidly when somebody is shooting at you. Attritional warfare is generally focused around destroying the enemy force through causing maximum casualties, often through massed firepower and grinding frontal offensives.

Classic Historic Example: The Battle of Verdun in 1916, when General Falkenhayn aimed to ‘bleed the enemy white’ by forcing the French to counter-attack his forces and massed artillery.1

Positional Warfare: A form of warfare defined by its emphasis on terrain and key spatial ‘positions of strength’ (hence the name). The focus of objectives is on these positions, rather than the enemy force. Sieges and war amongst heavy fortification and entrenchment are examples of positional warfare, which is usually slow and deliberate.

Classic Historical Example: The Western Front of the First World War from 1915-1917 is a classic example. Today’s Russo-Ukraine War is often cited as a modern example in which positional warfare dominates due to the current overmatch of precision firepower over available manoeuvre options.

Military Science nerds will inevitably quibble over the above definitions and conceptions. Nevertheless, I think it provides a rough shorthand guide to how these ‘forms’ of warfare are conceived, especially by western militaries on a day-to-day level.

The Debate That Shouldn’t Be?

These concepts are contested. In particular, many question whether ‘attritional warfare’ even exists at all, especially as a chosen set of tactics, and instead consider what people call ‘attritional’ warfare to simply be a natural characteristic of conflict.2

Regardless, it will probably seem obvious to say, but whether you are fighting ‘manoeuvre warfare’, ‘attritional warfare’, or ‘positional warfare’ is often context dependent. Furthermore, in terms of taking a ‘manoeuvre’, ‘attritional’, or ‘positional’ approach, all are obviously interlinked and it is often hard to separate them easily in historical analysis. All warfare is in some way attritional. Napoleon is remembered as a master of manoeuvre but was also famous for his massed artillery batteries used to cause rapid attrition in battle. Breaking the enemy’s will to fight (the goal of manoeuvre warfare) is often best done through inflicting significant attrition (e.g. the Gulf War), while manoeuvre is difficult in heavily built-up terrain, which often forces battle to have a more ‘positional’ flavour.

The Cult of Manoeuvre

Despite the above, in western military circles there has been something of a ‘cult of manoeuvre’ since the 1980s, which puts ‘manoeuvre’ as a state of warfare, and form of tactics, above all else. In particular, manoeuvre tactics, and creating a state of affairs in which manoeuvre warfare is the primary mode, is seen as the acme of fighting, especially as compared to attritional warfare. This is perhaps best summarised in the classic doctrinal refrain ‘we shoot in order to move’.

This directly translates into how western NATO militaries conceptualise themselves. Manoeuvre warfare as constructed is seen as requiring flair, initiative, intelligence and skill – the perfect art of war for a professional army of a liberal democratic nation of free-thinking individuals. This compares to ‘attritional’ warfare or even ‘positional’ warfare, which is therefore associated in such discourse with brutishness, wastefulness and unimaginativeness – the form of warfare used by, say, the conscript army of an authoritarian adversary. Indeed, one article describes ‘manoeuvrism’ as the ‘antithesis of attrition’. Whether this is true or not is less important than that is how it is seen. NATO militaries ‘do’ manoeuvre warfare; the bad guys, or incompetent militaries, ‘do’ attritional warfare. If western militaries find themselves fighting in an attritional or positional mode, they must ‘return’ to manoeuvre as the natural and desired state.

This is all well and good, and indeed effective tactical maneouvre can lead to rapid victory on the battlefield. The problem is that you can’t always realistically fight manoeuvre warfare in the way you’d like. As discussed above, context may dictate that you can’t – whether the military context or the political context. The latter is particularly important. Politics may require you to fight in a space and time not of your choosing, and one where the most suitable manoeuvre tactics are overridden by higher national demands. Cities that you would rather bypass require investment for political reasons; pieces of symbolically important but tactically useless terrain require defending above all else.3

Implications for Force Structure and Policy

‘Sblood, enough with military theory – what’s the real-life impact?

Fundamentally, how militaries conceive of themselves affects force structure, especially in resource-constrained environments, and can be used to excuse structural weakness.

The British Army focuses heavily on manoeuvre; its doctrine is based on the principle of the ‘Manoeuvrist Approach’ which is variously defined as ‘an indirect approach which advocates applying strength against enemy vulnerabilities’, or, interestingly, a ‘blend of disruptive manoeuvre and destructive firepower’. While this latter phrase might suggest a slight shift in approach, until recently it was honestly rare to hear British doctrine-types talk about anything but manoeuvre, and this still permeates the discourse.4

The concept that a relatively small force of highly-trained, intelligent soldiers can defeat larger forces of lumbering authoritarian enemies through rapid and effective manoeuvre is baked into the British Army’s (and wider British military’s) conception of fighting.5 This is convenient, because, with a historically-small army suffering from workforce and materiel issues, that is the only conceivable way the British Army could successfully fight an opponent.

And here lies the rub. Decades of cuts to personnel and equipment have continually reinforced the British Army’s conception of itself as ‘manoeuvrist’, as it is inconceivable that it could fight in an ‘attritional’ manner (as there is little for the enemy to ‘attrit’). The fact that effective maneouvre historically still requires significant mass and firepower alongside quality is often ignored. To suggest otherwise is to admit the politically-unacceptable truth that the British Army is not suitably structured for conventional war. Ironically, this self-conception of the British Army as an elite manoeuvrist force that ‘punches above its weight’ allows politicians to make even greater cuts. If we always ‘punch above our weight’, and quality is supreme, then there is always space for ‘cutting the fat’, even when there is no fat left and we are instead carving into muscle and bone.

General Sir Patrick Sanders, former Chief of the General Staff, retired (or was retired) early not long after he raised the politically-unacceptable point that in a conventional war some form of ‘citizen army’ would be needed, and that the basics of military organisation and land power needed to be emphasised over shiny things – memorably encapsulated in the phrase ‘you can’t cyber your way over a river’. These were basic, obvious points but were too much for the usual political discourse of defence in the United Kingdom. Following this brief detour, the Army has once more returned to regularly proselytise punching above our weight through quality and technology.

That takes us to another point – ‘manoeuvrism’ encourages, and indeed can morph into, an element of techno-fetishism, as new shiny technology offers nostrums to magically enhance a tiny force into an elite killing machine. Army leaders have been going on about drones, artificial intelligence, and cyber for years, without actually making any measurable impact to improve the structural foundations of the Army which those technologies might be able to enhance.6 This leads the Army into ludicrous techno-fetishist discourse – see the current cheery target of being x10 lethal in ten years. That is an utterly ridiculous policy target to set, not least because it is unachievable under current plans, and yet the Army has adopted it as an official talking point.7 Perhaps at my more uncharitable, I would also note that the current crop of senior officials are happy to make such claims, safe in the knowledge that they will not be around in ten years to take responsibility if it fails. ‘Manoeuvrism’ has enabled technological ‘boosterism’ of this kind, and therefore obscures effective decision-making and political debate on the thorny topic of force structure and resource allocation.

Conclusion

You might conclude that I think manoeuvre warfare is nonsense. I don’t. Furthermore, despite all the above, I actually quite like the Manoeuvrist Approach as a doctrinal principle. My issue is how ‘manoeuvre’ is socially constructed as a form of identity by western militaries, particularly in this case the British Army, and how that can impact force structure and policy decisions for the worse.

To finish, a historical example. The armies on the Western Front of the First World War designed and trained themselves to fight an aggressive war of manoeuvre. They did – for a few months, before context demanded that they dig in and spend the next few years fighting a positional, attrition-heavy fight they didn’t want and weren’t well prepared for. I don’t know what the next conventional war will look like and dearly, dearly hope it never happens. But we should be prepared for as many eventualities as possible, not just the one that fits a preconceived notion of who we are and how we’d like to fight.

Cracking Defence is a reader-supported publication. If you enjoy my writing, please like, share, subscribe, and if you are able, buy me a coffee to support my work. All and any support is hugely appreciated.

All the best,

Matthew

I’m about to discuss this below, but before the history fans jump on me – YES I KNOW that the classic view of Verdun as being planned as an attritional battle is contested. ‘Tis my point.

There should be distinctions made between attrition at the tactical and strategic levels. I certainly think arguments can be made for attrition as a strategy.

This is arguably one of the reasons that the Russo-Ukraine war has turned positional, as politically both sides are heavily focused on territory.

I remember once having a conversation with a British officer working in future doctrine development who informed me that the British Army simply wouldn’t find itself fighting in a positional urban battle as we’d bypass all urban terrain…….

This point is literally made in doctrine, by the way, as an ‘approach suited to a small, professional force’.

See how much Sir Nick Carter (boo) name-dropped ‘cyber’ during his over-long tenure.

I’ve had ‘no comment’ answers from British Army officials I’ve asked about this, which suggests, unsurprisingly, that they don’t have a serious strategy for reaching that target. Furthermore, when asked by the Defence Select Committee, one of the writers of the Strategic Defence Review answered that ‘we will know it when we see it’....🙃

Good essay on what is really a continuum of fighting options. Yes, people can get carried away in thinking maneuver warfare is a silver bullet method for making war less bloody and muddy. I would hope that maneuver can be enabled as the primary means of war. But sometimes events preclude that, as you address.

And yeah, I have to restrain myself from getting fanboyish about maneuver. The temptation IS great.

I loved the quote by General Sir Patrick Sanders. I remarked "When you Twitter a king, kill him" in response to the once-common notion that tyrants could be defeated with a good social network campaign as if maneuver online is enough.

Many things have their place in war. None are silver bullets.

Hits the nail on the head. How often do we hear about a feel good 'British way of war' utilising manoeuvre and allegedly superior quality and technology?

History shows almost every major war that has been a victory for Britain has been won with mass mobilised people's armies and mass at sea and later in the air; with said mass supported by a sophisticated logistical, financial and industrial base.

This doesn't diminish the generally good standard of training and historically innovative materiel British forces have had. However, any government serious about defence and serious about joining a large scale war needs to think and act quickly to (re)develop the mechanisms for rapid mobilisation and the industrial base to support it.