Why shoot a missile at someone, release a suicide drone, or fire an artillery shell?

Let’s look at two scenarios.

1) Russian invaders fire a salvo of Kalibr missiles at a Ukrainian airfield. Several are shot down by Ukrainian air defences, and a few miss, but others hit their target. The airfield suffers damage and a few Ukrainians are injured, though mercifully there are no fatalities.

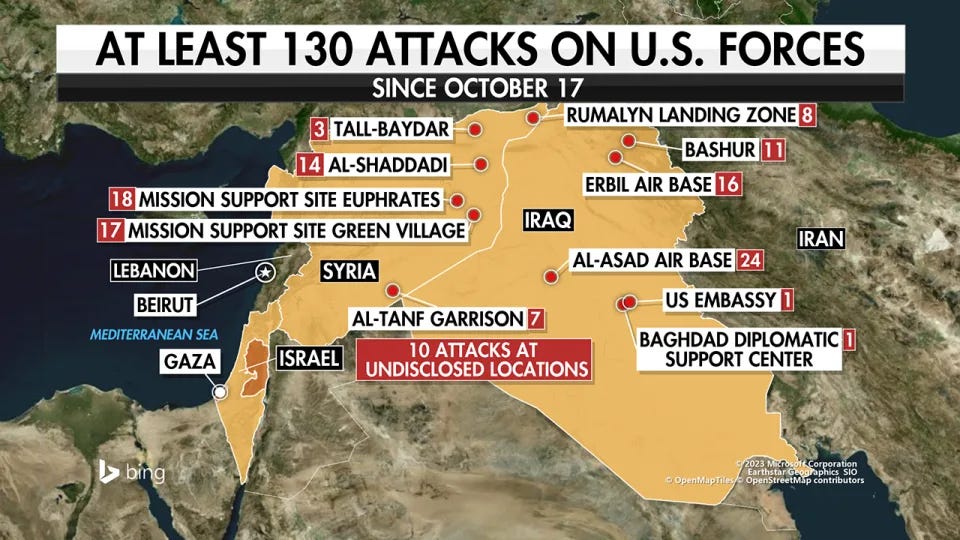

2) Iranian-aligned militias release a trio of one-way attack drones at a US base in Syria. One is shot down by US air defences, and another misses, but the final drone hits its target. The US base suffers mild damage and a few personnel are injured, though mercifully there are no fatalities.

Two outwardly very similar scenarios, with comparable outcomes on the ground. Nevertheless, the context of each scenario, and the reasons behind the employment of the weapons, differ significantly.

In the first – familiar to any watcher of the illegal Russian invasion of Ukraine – the context, and purpose, of the strike is primarily military. The desired Russian endstate is to degrade the airfield, reduce the Ukrainian ability to deploy aircraft, and therefore weaken Ukrainian airpower. The timing of the attack might be influenced by politics, but the strike is fundamentally a military-tactical event.

By contrast, the purpose of the second – emblematic of attacks taking place all over the Middle East right now – is not primarily military. Small-scale attacks launched independently at isolated bases with known air defence assets are not exemplars of exclusively-military reasoning. The perpetrators know full well that the attacks are unlikely to cause significant damage or casualties, and indeed, this is not the main objective. Instead, the primary purpose of these attacks is political, and they are meant first and foremost as a message: that the militias are actively part of an axis of resistance against the US, to prove solidarity with the Hamas cause, and to exert political pressure on casualty-adverse western governments. The publicised fact of the attack is more important than the physical result.

So, why does this difference matter, especially if the on-the-ground situation remains the same? In my view, it is important because the latter scenario – using targeted strikes primarily for strategic communication, rather than for battlefield effect – is becoming increasingly common globally, and poses dire risks in shaping how actors respond to escalation in crises.

Let’s look at one of the most prominent – and dangerous – ongoing examples of this phenomenon, which I call ‘Kinetic Messaging’. In recent discussions over cross-border exchanges of fire between Israel and Lebanese Hezbollah, much has been made of the ‘rules of the game’; a political situation understood by both sides, in which a certain level of kinetic violence is tolerated within ill-defined parameters as being ‘acceptable’ and below the threshold of a full-scale conflict. In this case, the exchange of fire is considered primarily an event of strategic communications rather than military tactics; Lebanese Hezbollah are signalling their ability to cause damage to Israel, and Israel are signalling their ability to respond in self-defence.

Of course, the issue with such ‘games’ is that there are no rules, nor are there any real parameters. Driven by political pressure, the actors will keep responding in escalating tit-for-tat measures until, suddenly, they find themselves undertaking actions that bring the prospect of war to within a knife’s edge. It is unsurprising that in recent weeks, reports of the ‘rules of the game’ have decidedly dropped off, substituted by very real fears of open warfare on Lebanon’s southern border.

This is not a problem confined to the current crisis in the Middle East. In Asia, North Korea not only launches ballistic missiles over its neighbours but on occasion fires artillery shells towards its southern rival as a show of force. China has released missiles that have landed in the economic zones of Taiwan and Japan as a political response to the visit of Nancy Pelosi’s visit in 2022, and routinely breaches Taiwanese airspace with warplanes. This month, Iran and Pakistan have exchanged tit-for-tat missile exchanges, ostensibly aimed at terrorist groups. This sort of behaviour is becoming normalised, and each time it occurs it further deepens the risk of serious miscalculation and conflagration.

This is why I emphasise the context of ‘Kinetic Messaging’; accepting a certain level of violence between states and/or state-like actors makes full-scale conflict more likely, not less. Such ‘games’ blur the lines between war and peace, keeping us forever in the dangerous ‘grey zone’ of conflict and leading actors to countenance actions that would have previously been considered beyond the pale.

The other issue with the rise of kinetic messaging is that it is difficult to combat effectively. If a state attempts to ignore it, it risks looking weak, indecisive, or callous as an adversary rains down deadly weaponry on their territory or people with impunity. However, reacting in a hostile manner to ‘deter through punishment’ raises the risk of significant escalation or losing the ever-important narrative battle to an opponent.

Hunkering down and developing the ability to counter such actions militarily is one option, as has been seen with Israel’s Iron Dome system. The danger of such a strategy is that, fundamentally, it does not solve the problem, and merely exacerbates the status quo; the long-term consequences can be tragic.

Conflicts and crises are solved through diplomacy; military force, ultimately, should be used as a last resort to set the conditions for starting negotiations. Kinetic messaging, however, makes the work of diplomats far more difficult. No serious military advantage is gained from strikes primarily meant to send a message; and the escalatory nature narrows the options and time available to negotiators. When exchanges of explosive weaponry are normalised as tools of strategic communication, lasting peace becomes less likely.

When it comes to this kind of strategic messaging, my basic reaction is “get used to it.” In the long history of human conflict, and I'm going back 5000 years into Mesopotamian and Egyptian history, the concept of a declared peace is a late arrival. The concept that one would be perpetually signaling hostility towards one's neighbors was the norm.

In ancient times, this was mostly done through nighttime raiding, or by punitive expeditions in which a king led a warrior band into the territory of the perpetual enemy, burned a few things, stole others, while the invaded population went into the hills to hide.

When you have to go in person to make a hostile demonstration it entails some risk. When you can simply lob a rocket or a shell toward your enemy, the cost maybe seen as lower.

BTW, the entity lobbing the shells is not only demonstrating continued hostility toward the enemy, but also strongly signaling to its own population, “Trust us! We will never make peace with those bastards!"

Bottom line: This is not a new development— there was a lot of it in the Cold War as well.