As part of the desire to reshape this blog for the informed general reader, I’m going to start writing some introductory explanations on elements of military capability. I promise this won’t be kit-fetishist; however, noting how expensive this sort of stuff is, I think that people should have some understanding of what their money is being spent on and why.

There is something specific in the imagination that comes to mind when the word ‘submarine’ is mentioned. Huge metal monsters gliding slowly through the deeps, guided by the otherworldly ‘ping’ of sonar. Tightly-cramped spaces full of men ghostly-pale from lack of sunlight. The fearful spectre of nuclear war haunting every action.

I’ve had a fascination with submarines since I was a boy – at one point I even wanted to join the Royal Navy’s Submarine Service, before I realised that a) I quite like the Sun, b) I didn’t want to spend my time in a crowded metal cylinder, and c) I didn’t want to live in a remote part of Scotland for the rest of my career.1 Despite this, I’ve never lost my fascination with these modern-day sea monsters.

Submarines are particularly vital military assets, and also hugely expensive. For instance, the new Dreadnought programme is estimated to cost over £31bn to design and construct just four new missile submarines. The suggested annual in-service cost of these submarines and their armament once completed will take up at least 6% of the defence budget. With such huge sums involved, I think it is important for the informed reader to understand what submarines are, what they do and why they cost so much taxpayer’s money.

What are Submarines

No egg-sucking here; a submarine is a vessel that travels primarily underwater.2 They’ve been used regularly in warfare since the First World War, and have proven critical elements of navies ever since.

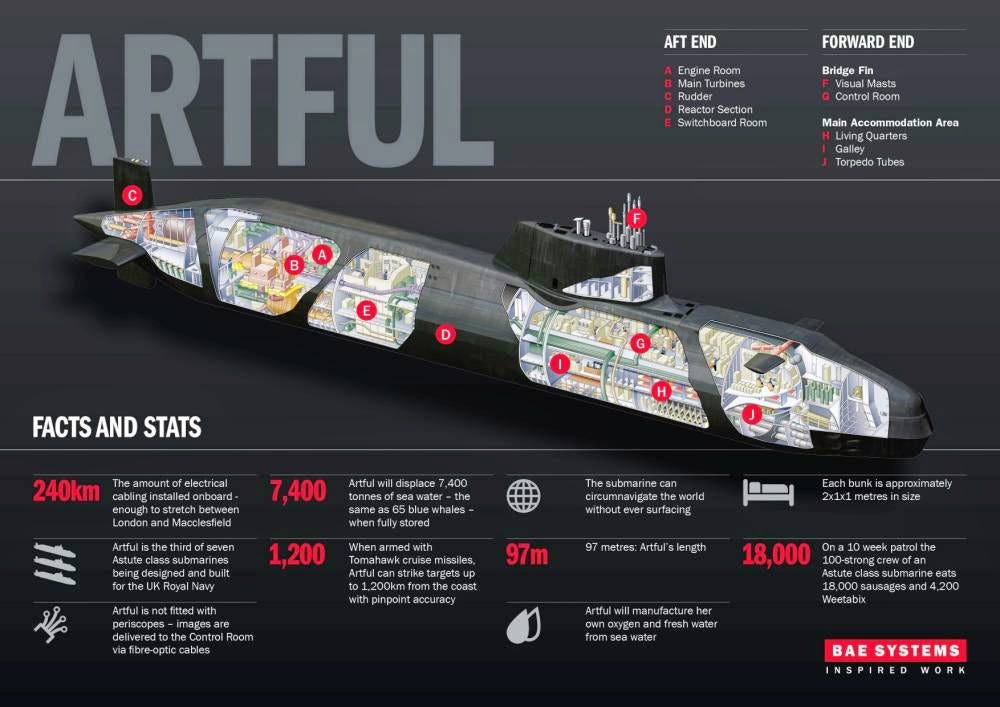

Submarines still look pretty much exactly what you think they look like – a long cylindrical body, a propeller, and a tall ‘conning tower’ with a periscope. Though they will still use periscopes occasionally, their primary sensor is sound. Using both passive and active sonar3 they detect other vessels almost entirely by hearing them, and then blow them up with guided torpedoes, missiles and mines.

In the modern age, submarines can be categorised into three rough types4, namely:

Nuclear Ballistic Missile Submarines (SSBNs): These are nuclear-powered submarines whose primary role is to carry nuclear ballistic missiles. Known sometimes as ‘boomers’ in the US Navy and ‘bombers’ in the Royal Navy. They tend to be very large – well over 15K tons. Their primary purpose is to hide from the enemy and await the instruction to launch their nuclear weapons – instructions that we all pray will never come. The current British variant is the Vanguard-class, which services what is known in British policy as the ‘Continuous At Sea Deterrent’ (CASD).

Nuclear Attack Submarines (SSNs): Often known menacingly as ‘hunter-killers’. These are nuclear-powered submarines but – critical distinction! – do not carry nuclear weapons. Instead, their primary role is to blow up other ships and submarines, usually with conventional torpedoes or cruise missiles. They tend to be quite large but still smaller than a SSBN. The Royal Navy currently operates the Astute-class and (as of writing) one old Trafalgar-class.

Conventional Attack Submarines (SSKs): Also known as ‘diesel-electric’ submarines due to the most common type of propulsion. These do basically the same job as SSNs but are not nuclear-powered in any way. As will be discussed below, this means they can be smaller, quieter, but have much less longevity underwater. A common SSK is the Russian Kilo-class.

Lots of navies have SSKs; very few operate SSNs or SSBNs. For example, the Royal Navy, US Navy, and French Navy have only SSBNs and SSNs. The Indian, Chinese and Russian Navies (boooo) have all three types. The Australian Navy currently has SSKs, but is transitioning to SSNs under AUKUS.

What Submarines do

The main military benefit of submarines is their stealth. Indeed, they are probably the stealthiest military assets available in the modern age, and are exceptionally hard to find. This means that, amongst other tasks, they are great at:

Reconnaissance and surveillance

Hunting surface targets and other submarines5

Keeping nuclear weapons safe

Surprise attacks, raids and ambushes

Covertly transporting special forces troops

Because submarines are so dangerous, the threat of one in an area requires an enemy to expend huge resource to find and defend against them. Finding a submarine usually requires multiple ships and aircraft continually patrolling and blasting an area with sonar. The alternative is to leave the area or risk being sunk without warning.

A famous example of this occurred during the Falklands War, when the sinking of the Argentinian ship ARA General Belgrano by the British SSN HMS Conqueror caused the Argentine fleet to return to port, unwilling to operate in an area containing a Royal Navy submarine. This highlights the enormous potential of submarines: a single action by a British SSN effectively neutered the threat of the Argentinian Navy for the rest of the war.

Nuclear or No?

The usage of nuclear technology on submarines – both in terms of propulsion and weapons – is controversial. The nuclear weapons question is a whole can of worms that I won’t delve into here, but suffice to say that if you are going to have nukes, putting them on a submarine makes a lot of sense if you want to protect them from the enemy.

Nuclear propulsion is another matter. The main benefit of nuclear-powered submarines is they can be very fast and that they can essentially stay submerged indefinitely. Indeed, the major limiting factor on a nuclear submarine staying under water is food supply (submarines can make their own water) and crew sanity. Hence, nuclear-powered submarines are perfect for navies that require their submarines to operate for long periods of time far from their home bases.

The downsides of nuclear propulsion from a military perspective are the extraordinary cost, regulation (e.g. not every port wants or is able to service a vessel with a nuclear reactor onboard), size, and a slight increase in noise. Conventional SSKs, which usually run off large electric batteries, can be a lot cheaper and smaller (and usually a bit quieter) but can’t stay underwater for as long. As such, SSKs are useful for navies that expect their submarines to operate in shallower waters closer to their home ports.

Why are Submarines So Expensive?

Modern submarines are some of the most complex machines ever built - nuclear-powered ones particularly so - full of extremely sophisticated and sensitive technology, each piece of which is essentially custom-manufactured. This in turn requires specialist shipyards and workers with very niche skillsets, and therefore incur very high training costs and salaries. In most cases, the small production lines of each class also prohibits economies of scale.

On a smaller scale, but still very relevant, submariners themselves cost a lot to recruit, train and retain; unsurprisingly it is quite difficult to find enough suitable individuals who want to work on submarines and who can stand the high-tempo and uncertain lifestyle that the job demands.

The Future

As the general battlespace becomes more ‘transparent’ thanks to the proliferation of precision sensors, submarines are going to remain critical assets due to their stealthiness. There is a lot of work going on regarding autonomous submarines and underwater drones; I’m sure they will exist in some form in the future, perhaps as ‘underwater wingmen’ to manned platforms. However, for now, the manned submarine still reigns supreme. Hugely expensive but undoubtedly powerful, they are essential for any navy wishing to bring the fight to the enemy at sea.

Submarine Fiction

Finally, for fun, my favourite submarine fiction out there:

- Das Boot: possibly the ultimate submarine media experience, about a U-boat crew in WW2. Watch the director’s cut in a dark, cold, cramped room and get a deranged German man to occasionally scream ‘ALARM’ at you for full immersion.

- Hunt for Red October: both the book and the film are absolute classics. Sean Connery is *chef’s kiss* as a Scotto-Russian Submarine Captain.

- Red Storm Rising: Also by Tom Clancy, this Cold War classic is heavily focused on the naval element of a hypothetical 1980s WW3. Lots of American competence-porn and 80s stereotypes.

- The Cruel Sea: One of my favourite naval films, about a British corvette crew trying to defend the convoys from German U-boat attack during the Second World War. Snorkers, good oh!

- Cold Waters: A submarine simulation game set during the Cold War. Great fun until you have three torpedoes chasing you on separate bearings, when suddenly it becomes extremely stressful.

All of the Royal Navy’s submarines are based in Faslane, in case you were wondering.

Fun fact: Submarines are always called ‘boats’ rather than ‘ships’. This is something that naval enthusiasts tend to get rather excited about.

Passive Sonar is the most common method and is essentially the submarine ‘listening’ for sounds. Active Sonar is the famous ‘ping’ when the submarine blasts out sonic energy to bounce off other objects. It is less-commonly used as doing so alerts enemies to the submarine’s presence.

For the pedants, YES I KNOW that there are technically more categories.

The latter point is particularly important regarding combatting the Russians, who heavily emphasise submarines in their naval forces.

Is there anything else you’d like to know about submarines? Have I got it all wrong? Let me know in the comments below!

All the best,

Matthew

Excellent article Matthew. It is vital that defence is demystified for the public. That would improve understanding, scrutiny and outcomes. Too much of defence is subject to groupthink due to the lack of broad informed debate. I look forward to future posts in the same vein.

A great primer. I’d add to your SSK section that underwater operations usually require the sub to slow down significantly.

While SSNs can easily keep up with a carrier group or move to intercept a threat underwater, the SSK will either have to travel on the surface (still slower than many surface combatants during war time) and risk detection or wait for enemy combatants to come to them (while snorkeling occasionally).