Powerpoint Commandos

An ode to the staff, and why it matters

Spare a thought, if you would, for the poor staff officer. He or she joined the military expecting a glorious adventure as a leader of men, winning medals on foreign fields and attracting partners like flies. Now, years down the line, they spend most of their time in soulless offices, creating ever-more elaborate powerpoint slides for a groundhog day of endless briefings. Their physiques have softened, they’ve been ditched by their partners, and their individuality starts to dissolve as they conform to an indeterminate norm in an ever-more desperate attempt to climb the greasy pole of promotion.

The role of the staff is one of the more under-appreciated and under-reported aspects of the military in the popular imagination. This is unsurprising, since drawing on maps, making powerpoint slides and briefing commanders generally makes for less exciting stories than the chaos of infantry combat or the tension of submarine warfare.1 However, the quality of the staff is absolutely critical to military operations, and the Armed Forces cannot run without them. As such, if anyone is to understand how modern warfare operates, they need to appreciate the role of the staff officer.

What is the staff?

All military operations are hugely complex, far too much for a single individual to understand on their own. Operations also generate a huge quantity of paperwork – orders, mapping, logistical tables, coordinating instructions etc. As such, commanders need a headquarters of dedicated individuals to assist them with the planning and execution of military operations – their staff.

The larger the military organisation, the more complex the operations it conducts and therefore the more staff it requires. This can range from around a dozen (battlegroup level) to into the hundreds (divisional and corps level).

Traditionally, most members of the staff are officers, due to the nature of the training and experience that officers receive; however military staffs also include non-commissioned personnel usually providing specialist support (intelligence, communications, etc). These days it is also not uncommon to find civilians as part of larger staffs, usually providing legal or policy advice.

How does a military staff operate?

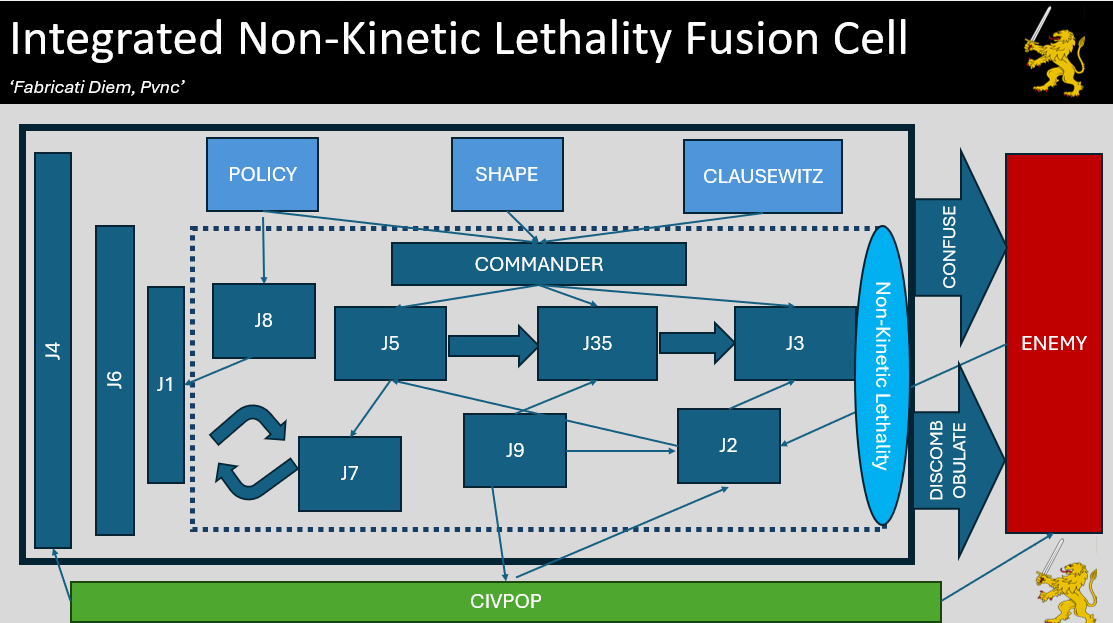

All professional militaries will have staff officers; how they are organised varies. For ease, I will explain the standard NATO staff organisation structure, usually known as the J1-9.2 Each staff function is designated a number, which provides an easy way of categorising and organising the various specialities required within the military staff. As such:

J1. Personnel. This is where you find your clerks, welfare people, padres etc. Never popular when they mess up people’s expenses.

J2. Intelligence. Full of pale nerds and people unhealthily obsessed with the minutiae of tank design. Social skills not required.

J3. Current Operations – in essence, managing the battle that is occurring now. Traditionally populated by two types: high-flyers who think they are the next Patton or Bill Slim, and incredibly over-worked stress balls. Hate J5 for coming up with insane plans that have no relation to reality.

J4. Logistics. Usually either stressed, grumpy, or stressed and grumpy. Will bleat ‘J4 wins the war’ at every opportunity.

J5. Plans or Future Operations. Planning ahead and coming up with future operations for J3 to execute, secure in the knowledge that J3 will get blamed if the plan doesn’t work. Beloved of self-described intellectuals and blue-sky thinkers.

J6. Communications/Signals. Ignored until the systems inevitably shut down and then everyone shouts at them until the tortured laptops and radios start working again.

J7. Training. Fume when real life gets in the way of their elaborately-planned training exercises. Home of big beefy physical training instructors constantly trying to keep all the flabby staff officers to do their annual PT tests.

J8. Finance. The accountants. Their default answer to everything is ‘no’.

J9. An oddity that can include Civil-Military Affairs, Media and Information Operations, Policy & Legal, or any combination thereof. 3 Generally considered weird Birkenstock-wearing lefties by the other branches.

There are also a few other common branches that don’t fit into the neat numerical category above, such as:

J35. The bridge between the J3 and the J5, hence pronounced ‘three-five’ not ‘thirty-five’. Meant to refine the insanity that J5 comes up with into something slightly more realistic for J3 to enact.

Joint Effects. Usually seen only in large joint headquarters and often linked to the J35, Joint Effects attempts to ensure synchronisation between a variety of different activities on the battlefield. In simple terms, how do we ensure that this bomb dropped, this missile fired, and this social media post all cohere and mutually reinforce one another? Tends to be full of preening Air Force wallahs and Artillerists, watched carefully by the lawyers.

The above gives some indication of how staffs are organised, but there are a multitude of variations and the larger headquarters can become bewilderingly complex.4

What does a staff look like?

Staff Headquarters can be anything from a handful of soldiers huddling round a map in the back of a land rover to gigantic ‘tented cities’ of hundreds of personnel. Staffs are usually busy, bustling places, running on fast-paced routines of innumerable briefings, working groups, and planning sessions. During operations, this will usually be 24/7, with the staff working in shifts.5 The main event of most days in an operational headquarters is the Commander’s Update Brief, a piece of theatre in which each department will, funnily enough, relay their updates to the boss. From there, direction will be given, and a new flurry of planning, orders-writing, and dissemination will occur.

The importance of the military staff

The military staff, fundamentally, is the brain of any military organisation. It coordinates, plans, and coheres all the activity of its subordinate fighting units, and ensures they have the support required to carry out their orders. Excellent staff processes are critical to modern warfare. A poor-quality staff will lead to disjointed and ineffective direction, with the potential for catastrophic loss on the battlefield. This is the case all the way up the chain; a really good staff at brigade level, for example, can be negated by bad staffing above or below them.6 Hence, the quality of staff output is a key capability that all militaries must strive to develop and retain.

Similarly, during wartime headquarters are critical assets that must be protected from the enemy. A successful strike on a headquarters can essentially behead a military formation, at least for a while. You may remember back in 2022/3 that the Ukrainians had distinct success in blunting the Russian advance thanks to their targeting of both logistics nodes and command posts. A lot of thought and effort must go into how to keep the headquarters as well protected as possible.

The future of the military staff

Military staffs have utterly ballooned in recent decades – much larger than their predecessors in the Second World War, for instance. While this is partly due to the greater complexity of certain aspects of warfare, it is also due to the ever-more detailed data and plans demanded by military commanders. The problem with this is twofold: resource-burden (people, power, supply, sheer space) and survivability. In simple terms, big headquarters hoover up a lot of resources, and are also much easier to spot and target by the enemy, especially in a world of long-ranged precision weaponry.

As such, modern militaries are looking hard at ways to reduce the vulnerability of headquarters. One is to keep them both dispersed and mobile – it is much harder to target a headquarters on the move, the elements of which are not always in the same location.7 Another is to camouflage them – usually by placing them in built-up areas where their electronic signature can be somewhat masked in the urban noise. There are multiple trade-offs, not least that the more survivable you make a headquarters, the less efficient it generally is. However, a targeted and destroyed headquarters is the least efficient of all, so sacrifices have to be made.

New technology is very likely to play a role in making headquarters both smaller and more efficient. Artificial intelligence especially has already made an impact on military planning and decision-making processes, though with arguably mixed results. However, if implemented properly, AI could lead to much more efficient and smaller headquarters, if nothing else by assisting with predictive modelling and clearing a lot of the grunt paperwork that is required in modern staff processes.

Conclusion

The staff is an unloved but critical function in modern militaries. It is the brain of the military beast, directing, controlling, and feeding the fight. Developing an effective staff requires dedicated training, smooth processes and strong professional culture; it isn’t easy, nor does it happen overnight.

So, next time you consider the military, don’t neglect the humble staff officer. They might be fat, boring and unglamorous, but they are vital to your nation’s defence.

Any further questions on the staff, or military planning? Any disagreements with my stereotyping from the veteran staff officers amongst you? Let me know in the comments below!

All the best,

Matthew

One good (if slightly eccentric) example is The Road Past Mandalay, which is the memoir of one of Bill Slim’s principal staff officers during the Burma Campaign. Well worth a read.

‘J’ refers to Joint, e.g a headquarters containing all of the services (Army, Navy, Air Force, etc). The letter changes depending on service and country: in UK terminology you will usually see ‘G’ for Army, ‘N’ for Navy, and ‘A’ for Air Force.

Big NATO Headquarters have now split the Strategic Communication wallahs into their own seperate J10, but this is not fully adopted across the board by national militaries.

For instance, I once worked in a headquarters department named the CJ39, meaning that it was the 9 (Civil Affairs) of the 3 (Current Operations) of a Joint (all services) and Combined (multinational) Headquarters. This same Headquarters had a ‘CJ33’ - as in the ‘Current Ops of the Current Ops’. Confusing!

Or simply not sleeping, as it may be. Unsurprisingly, the supply of coffee is a critical asset that must be protected if the staff is to function…

There have been multiple reports that one of the issues Ukraine is facing is its lack of any firm structures above that of Brigade, and therefore issues with staffwork at the higher level. Furthermore, new Brigades formed have very little institutional staff knowledge, leading to poor planning and execution.

Dispersal and mobility were practiced in the Cold War as well, but are even more pertinent today.

Served as an NCO in the 3 shop for 2/75 Rangers for 4 years. I could type! Most Rangers back then couldn't. Troops who wanted to be Rangers didn't want to type; typists didn't want to be Rangers. This was even more dramatic with our Ranger cooks! We incentivized them to stay in the unit by sending them to a variety of schools (Ranger, Jumpmaster, Scuba, etc.). In large "flat" MOS's like cooks getting the extra promotion points for having attended schools made a huge difference in their promotion rate throughout their career. And having outstanding food waiting back at the barracks provided significant incentive to the troops in the field. One last aside - this was where I had my first laptop, an Osborne. It had 2 floppy drives - one for data and one for the program. It was AWESOME to prepare/modify operations orders with on the fly. I even jumped it once "just because" (rode it in to avoid damaging the unit). That was 1982 . . . Also learned how to transmit faxes over AM radio! Lot's of lost skills from that time period.

Another really good article. If you are interested in generalship, and how large armies are led and fight then understanding the concept of a 'staff' is vital. No large military operation can be conducted without good staff work, for example the Macarthur's very successful Inchon landing during the Korean War relied on USMC and USN staff officers that had gained their experience in WW2. It is also worth studying the way the German staff system evolved and worked, creating a stream of highly intellectual officers that encouraged innovation. Being on the General Staff was an honour, and it is also interesting how German leaders often took their key staff officers with them as the moved up the ranks creating very cohesive and high-performing teams. Understanding how a staff works is vital for understanding how an army actually functions. Great article.