Psywarriors and Mindbullets

A primer on Psychological Warfare

‘Hence to fight and conquer in all your battles is not supreme excellence; supreme excellence consists in breaking the enemy's resistance without fighting.’

Sun Tzu

Psychological Warfare. Has a nasty edge to it, no? Emanates thoughts of cold, damp basement bunkers, manacles, white noise, psychopathic authoritarian scientists and faceless intelligence officers. The Ipcress File and brainwashing. Cold War weirdness and modern-day troll farms. Wet work.

In truth, much of what we label ‘psychological warfare’ is rather less fantastical and more akin to advertising, entertainment and journalism than to The Men Who Stare at Goats or the exploits of Harry Palmer.1 This does not mean that it isn’t still a hugely interesting topic, and a key component of hybrid warfare both on the tactical and strategic level.

Clausewitz tells us that an enemy’s powers of resistance are the product of two factors: the sum of his available means and the strength of his will. Psychological warfare aims to target and crack the latter. War is a human phenomenon, and the side that loses the will to fight loses the war.

Some definitions

NATO defines psychological operations (we don’t like the term ‘psychological warfare’ anymore because it sounds icky) as ‘Planned psychological activities using methods of communications and other means directed to approved audiences in order to influence perceptions, attitudes and behaviour, affecting the achievement of political and military objectives.’

The US Army, which currently prefers the term ‘Military Information Support Operations’ rather than psychological operations, defines it as thus: ‘Military information support operations (MISO) are planned operations to convey selected information and indicators to foreign audiences to influence their emotions, motives, objective reasoning, and ultimately the behaviour of foreign governments, organisations, groups, and individuals in a manner favourable to the originator's objectives.’2

All quite wordy, but in simple terms – psychological operations aim to create behavioural changes in audiences. This could literally be anything – getting them to move in a certain way, to buy something, to vote for somebody, to fight harder, to not fight at all, etc.

A question to be answered – what is the difference between psychological operations and propaganda? Indeed, many of the techniques and principles are the same. For me – and I stress that this is a personal definition – it is dependent on audience. Propaganda is meant to be targeted at your own forces and population, while Psychological Operations are aimed at foreign audiences, whether hostile or not.

Fighting Psychological Warfare

When most people consider modern-day psychological operations – or the related term, information operations – they will probably think of social media and the internet.3 Indeed, this is a prime information environment in which to conduct psyops, especially as an increasing proportion of our time is spent online.4 It is undoubtedly true that the internet has made it very easy – and cheap! – to disseminate messages to a wide audience. However, psyops take multiple forms, many of them quite old-school, not least:

Leaflets, posters, and handbills

Newspaper articles and opinion pieces

Word of mouth

Text messages and phone calls

Graffiti

Protests and rent-a-mobs

Blackmail

Christmas Trees (yes, really)5

Indeed, physical psyops can be just as effective – if not more so – than online or electronic psyops; the acme is to combine all measures into one hugely powerful message. Imagine the effect if you received a personalised threatening message not just through social media, but also via text message and graffitied in red letters on your front door – all on the same day. If that wouldn’t have a psychological effect, I don’t know what would!

White, Grey, Black; Dis, Mis, Mal

You will sometimes hear about white, grey, and black psyops, relating to whether the activity is attributed to an actor and the truthfulness of the information conveyed. To be honest, these are quite old-school definitions and, in my opinion, not always that useful. More pertinent to the lay reader are the actual definitions of dis/mis/mal information:

Disinformation: false information, knowingly shared maliciously.

Example: Russian trolls creating and sharing fake news about a British politician.

Misinformation: false information, but the disseminator believes it to be true.

Example: ordinary person shares the above information about the British politician on their social media without verifying it.

Malinformation: technically-true information, but twisted out of context so that it conveys a false or hostile narrative, knowingly-shared.

Example: Russian troll promotes an image of a British politician raising their hand in front of a crying child and promoting it as evidence that the politican hit the child.

It’s worth knowing these definitions, as people will conflate them and bandy them about to the point to which it gets confusing.

Quality over Quantity

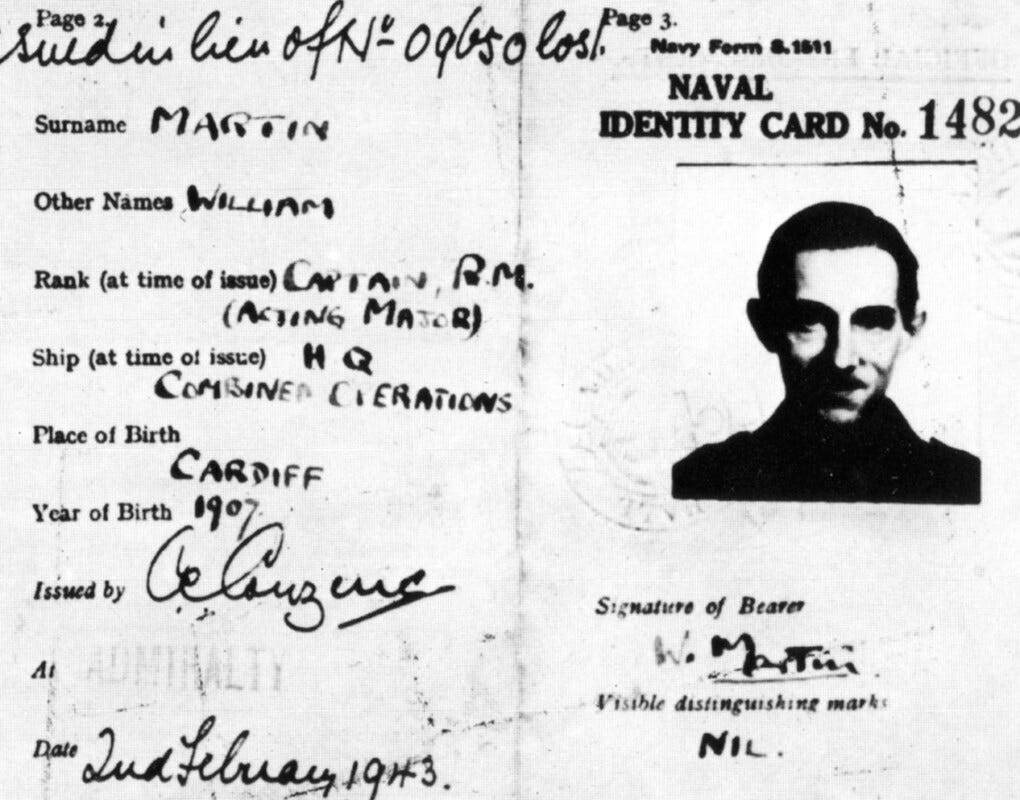

While there is much said about the utter flood of disinformation posts online, a lot of the best psyops are quite targeted. As any advertiser knows, it is generally best to focus on a tightly-defined target audience than wildly spewing content into the aether. For example, if you are trying to stir up disorder in an area, it is often best to focus your efforts on radicalising a small group who will then go out and protest. In a military context, it is usually more useful to aim psyops at a weak or disunited unit than spraying leaflets and memes across a wider front. A small-scale but well-targeted psyop can have huge effect – one of the most famous historical examples, Operation Mincemeat, deceived German intelligence to the point of changing troop movements by placing a dead body and some faked documents off the coast of Spain.

Measurement of Effect

Determining the actual effect of psyops, and separating correlation from causation, can be difficult, especially perception-based operations. This is why the best psyops often have a concrete, physical goal in mind – e.g. ‘convince x number of soldiers to desert’ rather than ‘convince x number of soldiers that their commander is an idiot’. This is not to say that perception-based psyops aren’t effective – the tidal wave of Russian psyops hitting European shores over the last decade being an obvious example – but are much more long-term in effect and harder to accurately quantify as a success.

Who conducts Psyops?

The organisations responsible for conducting psyops varies by country to country, and by the overall aim. Most militaries now have some form of psyops or information warfare unit – 77th Brigade is the UK MOD’s principle psyops organisation, for example. Ministries of Foreign Affairs have historically (and still do) conduct psychological operations, like the UK Foreign Office’s Cold-War era Information Research Department, while intelligence services might also conduct secret psyops. Non-state actors, whether independent or associated with states, also conduct psyops, including criminals, paramilitaries, private businesses, and terrorist organisations.6

The focus of these entities depends on the higher priorities of the organisation. For instance, military psyopers will often focus on tactical-level activity in support of wider military operations, while those working for a Foreign Ministry might focus on wider strategic communications in host countries.

It should be remembered that these psyops, regardless of actor, do not necessarily need to be malicious! Convincing large numbers of refugees to move off a dangerous road onto safer routes would be an example of positive psyops, as would counter-psyops aimed at debunking disinformation disseminated by adversaries.

Psyops today and in the future

Psyops are an effective asymmetric tool, and one that our adversaries – especially Russia – deploy effectively against us. This does not mean that they are always successful, nor that we can’t fight them back in the psychological space. Ukraine – a country whose culture was little-known to many outside its own borders prior to 2022 – has proven adept at fighting Russian ‘cognitive warfare’ and conducting its own psyops and information operations. Western liberal democracies can learn a lot from Ukraine - and other nations such as Taiwan - in how they tackle this threat.

Psychological warfare is not a new phenomenon - we’ve been doing it as long as we’ve been fighting each other. This does not mean that it stands still. Social media has evidently opened up huge new avenues for reaching audiences directly with psychological operations. Furthermore, with the advent of widespread generative artificial intelligence, the ability of actors to create effective, convincing psyop products at an extremely rapid rate (especially online) will only increase; whether AI can in turn help counteract this remains to be seen.7

Conclusion

Psychological warfare is a key component – perhaps the key – in the hybrid war our enemies are waging against us, and it behoves us to understand it as educated citizenry. I hope here that I’ve somewhat demystifyied the concept and outlining the key tenets of how it is conducted, especially considering how often it seems to be misunderstood by the general public. As ever, a strong defence always starts with a clear understanding of both the threat and the opportunities available to us.

All the best,

Matthew

Unsurprisingly, a lot of the psyop specialists mobilised during the First and Second World Wars came from the advertising, media, and creative industries.

I once asked a US Army Psyop specialist about this. His answer was, in short, that the US Congress gets excited – and not in a good way – if you start mentioning the US military conducting psychological warfare. It’s a political thing.

‘Information Operations’ is a complex term with a variety of broad and niche definitions. In a NATO context it actually refers to a staff function more than anything else.

For the pedantic ex-US Army guys amongst you, yes, I know you prefer the term ‘PSYOP’ as a collective noun. I’m a Brit and I don’t.

Operation Christmas is a good example of a creative and arguably-positive psyop. It was considered a success by the Colombian goverment as well.

Da’esh (ISIS) were in particular exceptionally good at psychological operations during their height of 2014-2018. Mosul fell in 2014 partly thanks to excellent Da’esh psyops convincing the Iraqi security forces to desert.

It should also be noted that a very effective form of information warfare - and therefore eventual psyop - would be to start polluting AI training data with false and malicious input.

Great introduction and summary. One of the things that has always concerned me is how you counter psychological warfare aimed at your forces or population in an effective and efficient manner. Once upon a time this could be done thru official news releases and campaigns, published or broadcast by government agencies and/or news organizations. The problem is that many of these sources have damaged their credibility to such an extent, by actually lying to and blindly repeating what is clearly propaganda from other sources as “news”, that they are not very effective anymore.

I posit that the average citizen is very skeptical these days and more than a few people do not believe mainstream media or official sources at all any longer. Restoring credibility takes a lot of time and effort. The first steps are to get the facts, stop spinning things to suit an ideological agenda, stop lying and act like actual, old school journalists.

Matt, I know PSYOPS are not your specialty, but I would like a serious analysis of Trump's messaging from a PSYOPS perspective. Divide and confuse the United States? Divide and confuse the world?