Those who follow European defence developments may have started to notice increased discussion of ‘JEF’ over the past few years. Rather than being the name of a mysterious individual somehow connected to European security, JEF is actually the acronym for the Joint Expeditionary Force, a northern European alliance. A slightly unusual – and often misunderstood – organisation, the JEF is worth discussing for its role as a European defence initiative which does not involve the United States, especially at a time when the incoming US administration appears distinctly eurosceptic and suspicious of NATO.

For full disclosure – I used to work at the JEF a few years ago, so I have some fondess for the organisation, and (hopefully!) some understanding of how it works.

What is the JEF?

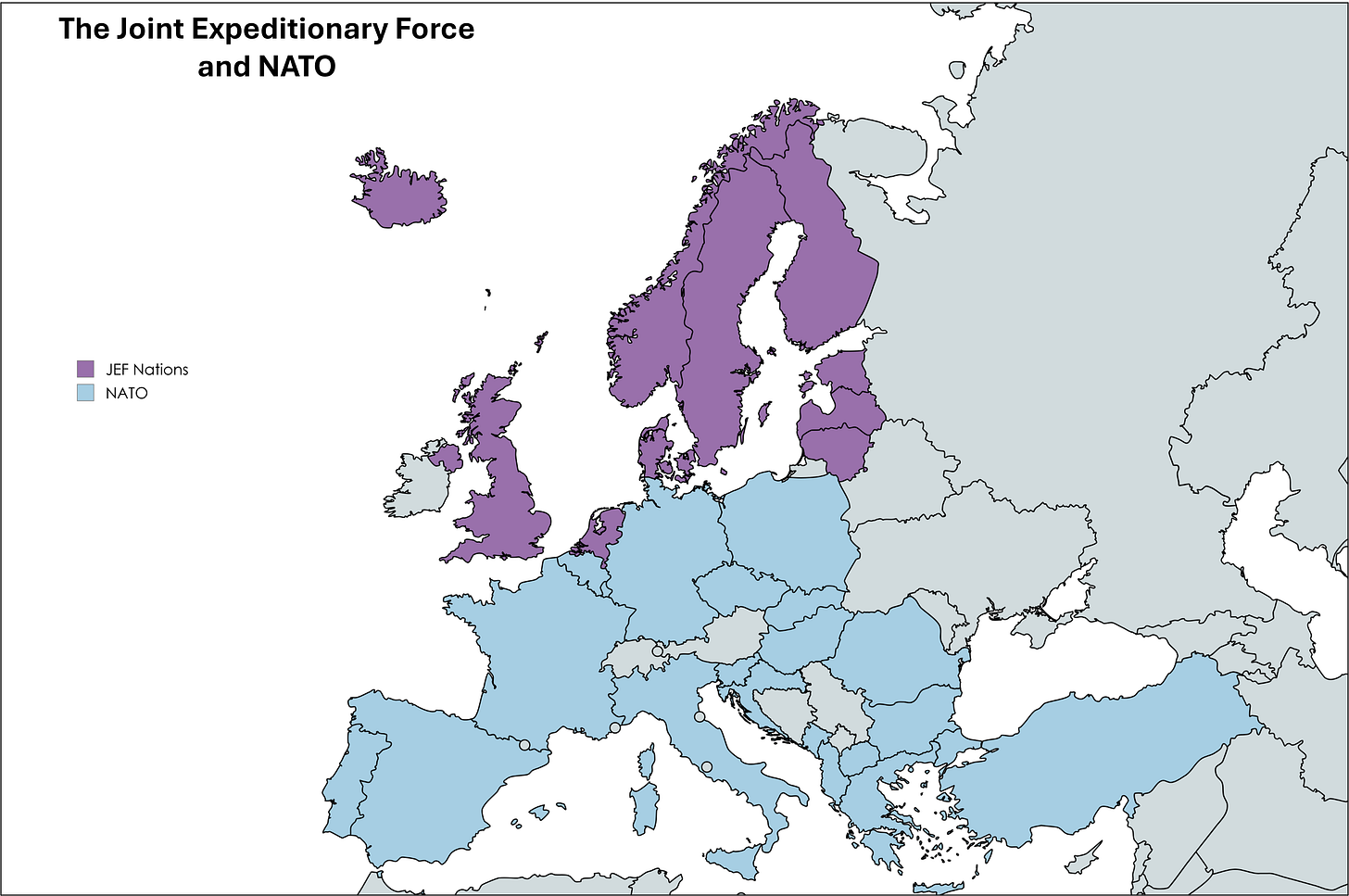

The Joint Expeditionary Force is an alliance of Northern European nations – in essence, Scandinavia (inc. Iceland), the Baltics, the Netherlands and the UK. Set up in 2014, the JEF was conceived as a flexible partnership between like-minded countries (‘the beer-drinking nations of the North’ is a favoured description of British generals and ministers) that could rapidly respond to crises in a coordinated manner.

So, you might ask, is the JEF like a mini-NATO? Not really. The JEF is a far looser and more fluid organisation. Its most interesting characteristic – in distinct opposition to NATO – is its ‘opt-in’ function. In simple terms, the entire membership of the JEF does not need to agree for JEF activity to take place – if two or more members wish to act, they can do so under a JEF banner. As the UK is the framework nation, providing much of the permanent workforce and day-to-day operations, in reality this must be caveated with ‘any members + the UK’ but the principle remains. This is very different from NATO, where unanimity across all member states is key. The original intent behind the JEF was to provide another method by which western allies could work together to counter threats; while the usual suspects in NATO dragged their feet (let us mention no names…) or put up blockers, the JEF would be able to provide a nimble initial response to crises.

Due to this policy, the JEF is a far, far, far smaller beast that NATO. Functionally, it is a 2* joint headquarters (i.e., led by a 2* General, so broadly equivalent to an army division1), and has no permanent forces assigned other than the (mostly British) staff of said headquarters. This is something often forgotten by certain enthusiasts, who think that the JEF is a bigger organisation – with far greater authority – than it actually is.

What does the JEF do?

Much of the regular activity conducted by the JEF is routine. A number of drumbeat exercises between member state militaries occur under JEF banners, the JEF runs its own big headquarters exercises once or twice a year, and there are regular ministerial and Chiefs-of-Defence-Staff (CHODS2) meetings. The most notable activities conducted by the JEF are ‘JEF Response Options’, which have been activated in 2023, in 2024 and most recently in the first week of 2025 (just a few days ago, as of time of writing). In all cases, the JEF cohered allied activity to assist in the protection of maritime critical national infrastructure. This should not be confused with JEF command of the forces; instead the JEF HQ provides the coordination and coherence of nationally controlled assets. This is quite different from the NATO system, in which the Alliance formally takes command of military assets, with the ability to issue orders etc.

Has the JEF been overtaken by events?

The JEF was born in an era when NATO was even more slow and sluggish than it is today3, and when Sweden and Finland were neutral countries. It was also partly meant to contribute more to ‘out of Europe’ crises. The world is different now. Sweden and Finland are both full NATO allies, the focus is very much on European security, and NATO (though still execrably bureaucratic) has found new life and momentum.

In particular, the Supreme Allied Commander (SACEUR – the top military dog in NATO) has greater authority to deploy troops under his own authority in response to crisis. The new Allied Reaction Force (ARF) is a body of troops ready for rapid reaction under the direct command of NATO. As such, some of the original advantages of the JEF – the flexibility and speed of response – are arguably somewhat moot.

The question then poses itself – why would the beer-drinking northern states work through the JEF when they could instead draw upon the resources of the immeasurably more structured and powerful NATO, an alliance that they all now belong to?

What could the JEF do?

A great advantage of the JEF is that, broadly-speaking, its members are amongst the most forthright in NATO, especially when it comes to countering Russia. It doesn’t take much to convince the Finns or Estonians, for example, to get tough with their Eastern neighbour. Due to this, the JEF’s flexibility still provides a significant advantage, especially if operating in the organisation’s core regions of the Baltic Sea and High North. This is also true due to the inherent politics of any NATO activity. SACEUR may very well have operational command of the ARF and the on-paper ability to deploy it (within caveats) when he sees fit; but I find it unlikely that this would happen on a major scale if there was serious political pushback from certain NATO members.

There is also the simple case of divided responsibilities. Growing attention is being paid to South-Eastern Europe as a potential flashpoint; if elements of the ARF have to deploy to this region in a crisis scenario, the JEF may have to step up to provide enhanced deterrence in the North.

On a more mundane level, the JEF offers the potential as a ‘test bed’ for trying out different forms of European defence integration and cooperation. This is a major argument put forward by a recent RUSI paper on the JEF (I don’t agree with all of its arguments but it’s well worth a read for those interested). A smaller, nimbler grouping of European countries who are usually on the same page, the JEF can adopt new methods, processes, and systems more quickly, which then might be tried out and then expanded to the rest of NATO. This would be particularly useful if (as is likely) NATO is going to become ever-more Europeanised.

Should the JEF be expanded?

There is often discussion over whether JEF membership should be extended to other countries. The most common suggested members are Germany, Poland and – more left-field – Ukraine. In general, I happen to believe that broader membership isn’t necessary at the moment, and I think that most JEF members would agree.

Broadly, adding more member states increases complexity and generally reduces flexibility. Though the JEF is an ‘opt-in’ organisation, it works at its best when all nations are aligned. The JEF is also – though not explicitly – becoming primarily concerned with the defence of the High North and the Baltics. As such, there would be little benefit that Ukraine in particular would add – or receive – as a member (on a more prosaic level, there would also be issues over security classifications, access to systems, etc).

Whether to invite Poland and Germany as members is an interesting question. While they are both Baltic Sea states, it is generally considered that both are more aligned to central European defence concerns – i.e. Russian tanks crashing down the European plain.4 They are also both quite large countries. This is not a particularly altruistic point, but the UK is unlikely to want other big defence players muscling in on a club that they are the most powerful member of. Even when ignoring the UK’s private interests, the introduction of new large players may lead to greater political and institutional frictions in an organisation which, at root, is a 2* headquarters.5 Fundamentally, I think the JEF needs to prove its value at its current size, rather than rush to add new members.

JEF’s Future

The JEF suffers from the fact that there is a lack of clarity over its role. Ironically, this is particularly so in the UK, despite us being the framework nation. Due to the structural design of the JEF, even if all other parties wanted to do more with the organisation, if the UK drags its heels any impetus will die out.

As such, the JEF currently stands at a bit of a crossroads. It could well be given a boost of policy interest and money (forever a concern) and become one of the key defence arrangements in Europe, truly complementary to NATO. On the other hand, it may slowly wither into an over-engineered talking shop and make-work headquarters, forever a nuisance that politicians give lip service to but never fully support. I’d hope the former would occur; indeed, the election of the decidedly eurosceptic President Trump may well give new impetus for European defence arrangements that do not include the United States. We’ll see how the JEF evolves over the latter half of the 2020s.

What are your thoughts on the JEF? Destined for a bright future or slow decline? Let me know below.

All the best,

Matthew

It is not an easy analogy as a joint headquarters, but very roughly a division usually consists of around 10-20K soldiers.

As a young staff officer, it took me about three months to pluck up the courage and ask what a ‘Chod’ was….

For Cold War enthusiasts – in case you missed it, the ‘Suwalki Gap’ is the new ‘Fulda Gap’ of European defence concerns.

Interesting fact: Germany was designated a NATO framework nation (alongside the UK and Italy) back in 2014 under the Framework Nation Concept. However, very little is said about either the German or Italian frameworks, though admittedly they were both far less ambitious than JEF.

Thanks for the informative article, I really enjoyed it and found it quite thought provoking. Recently, NATO nations are deploying more often in the Pacific supporting 'freedom of navigation' patrols and exercising with nations like Japan and Australia. Do you see a role for JEF is the Indo-Pacific region?

That first link tho 👁️👁️