Defending Small Rich States

On the new Defence Policies of Ireland and New Zealand

‘Ireland is no longer protected by its geographic position and history of military non-aggression.’

‘Where we as New Zealanders once saw ourselves as largely protected from threats by geography… threats are reaching New Zealanders more directly.’

Everyone, it seems, is waking up to the fact that the world is becoming more tense and fraught with geopolitical danger that it has been for decades.1 This includes nations that for a long time seemed quite far away, whether politically or geographically, from humanity’s acute conflict trouble-spots.

Two such nations are the Republic of Ireland and New Zealand, both of which have recently committed to significantly improving their defences. I find the comparison of these two nations interesting, not least because they are examples of relatively small but rich nations that have not historically focused on defence as a priority.2 Both Ireland and New Zealand are also of rising geopolitical importance, like many smaller nations, and therefore it is worth knowing something about their defence postures.

Caveat emptor – I’m neither Irish nor Kiwi, and won’t pretend that I have a detailed understanding of the politics of defence spending in either nation, so I’ll try to avoid any talk of domestic political concerns. With my backside now suitably covered, let’s dive in.

New Horizons for Defence

Ireland has a long pedigree of overt military neutrality and has kept a very small defence establishment focused on homeland security and a honourable tradition of contributing to United Nations peacekeeping efforts.3 Ireland has maintained its defences on a very low level of spending – approximately 0.4% of GNI.4 This has now been acknowledged as unsuitable, especially as Ireland is unable to monitor its own airspace effectively, and has tacitly relied on airspace interception from the UK’s Royal Air Force. Reform of this posture is underway, starting with the 2022 Commission on the Armed Forces and culminating with the 2024 Defence Policy Review. This has led to the Irish government accepting what is known as ‘Level of Ambition 2’ – a set of recommendations for upscaling and improving the defence of Ireland – with the stated desire to scale up to ‘Level of Ambition 3’ (including fighter jets and a larger navy) in the future. There is also appetite for Ireland to drop its long-standing requirement for a UN mandate to deploy troops abroad, providing the country with more flexibility in how it uses its defence forces.5

New Zealand also has quite a small defence force, though with more muscular ambitions than Ireland. The country has historically supported the UK, Australia, and the United States in various conflicts (including most recently in Afghanistan and Iraq), contributed to UN missions, and remains a member of the exclusive Five Eyes intelligence club. As such, New Zealand’s military is quite expeditionary, focused around providing small packets of naval, land, and special forces power to coalition endeavours.

Similarly to Ireland, New Zealand has published a number of documents detailing a change in posture, including the country’s first ever National Security Strategy, and most recently a Defence Capability Plan. Defence spending is also expected to almost double from around 1% to 2% of GDP.

Clear-eyed Defence Policy

British defence policy documents can be maddeningly imprecise and grand-standing, continually engaged in linguistic manoeuvring in order to avoid media and political upset. Everyone is our best friend and most important partner; we will be able to do everything everywhere all at once with no additional cost; we are always the leading European power in NATO because we say we are as well as a significant ‘Indo-Pacific’ power, et cetera et cetera. British defence policy comes with significant political baggage that trends towards evasive, unclear language.

By contrast, reading the defence policy documents of both Ireland and New Zealand is quite refreshing, not least because they are reasonably concise (especially that of New Zealand). Both have clear defence priorities and set out what they intend to do to resource them.

Both nations, unsurprisingly considering their island geography with large exclusive economic zones, see their primary threats as being maritime (including air) and ‘hybrid’ – including attacks via cyberspace or on critical national infrastructure. While neither nation is a member of a military alliance as deep or extensive as NATO, both emphasise the importance of strong international partnerships – focused around the European Union in the case of Ireland, and Australia and the USA (‘ANZUS’) for New Zealand.6

The means to greater defence are also clearly laid out. Ireland, starting from a very low baseline, puts its number one capability priority as establishing an integrated monitoring and surveillance system – i.e. connected sensors such as radar and sonar to ensure that Ireland can detect and monitor potential threats to its territory and especially to its waters. This is then followed by boosts to cyber security and air defence, as well as a healthy focus on renewing defence infrastructure and improving recruitment and retention for the severely-undermanned Irish Defence Force.

New Zealand also emphasises enhanced maritime surveillance and patrol using both classic vehicles and drones. However, the 2025 Capability Plan is also a lot ‘crunchier’ than the Irish Defence Policy Paper, with the priority investment going to ‘enhanced strike’ – i.e. more missiles, with an emphasis on anti-ship weaponry. This gives you an indication of how closely New Zealand sees itself integrating with Australia, which has also emphasised longer-ranged weaponry, especially at sea, in its recent defence strategy.

Both Ireland and New Zealand have the advantage of minimal political baggage regarding the need to display themselves as premier military powers (though of course each will have their own defence-related political hangups, Ireland especially). In both cases, this has led to a clearer understanding of needs and the ability to prioritise effectively when it comes to defence strategy.

Acquiring Capability

Smaller nations rarely have a full-spectrum defence industry capable of supplying all their needs. Even Finland and Singapore – two heavily defence-focused nations – cannot supply all their military needs domestically.7

Neither Ireland nor New Zealand has a significant domestic defence industry, and that means for most of what they need they will need to go shopping abroad.8 This is in stark contrast to the UK, which has a significant domestic defence industrial base, and considerable political requirements to keep it sustained and regenerated.

This can be a bit of a double-edged sword; on one hand, not having much of a defence industry means that you are reliant on other nations for providing you with weapons and equipment. On the other hand, you have less domestic political pressures to always ‘buy local’ – often at the expense of efficiency, as seen in the case of British procurement disasters over the last few decades. Instead, smaller nations can shop around a bit on the market for the best options – at least in theory.

Other than cost, the major constraint on Ireland and New Zealand is who they want to work with. In New Zealand’s case, the choice is more limited – if they want to be interoperable with Australia (which mostly runs with American equipment), then there will be a narrower range of potential options available. For neutral Ireland, the field is far more open, though diplomatic ties and the fact that Ireland has signed up to the EU’s SAFE scheme means that buying predominantly European equipment is likely. If Ireland decides to go the full mile and invest in a squadron of fighter jets as suggested under ‘Level of Ambition 3’, it would be very interesting to see what platform the Irish decide upon.9

Geopolitical Relevance

Both Ireland and New Zealand are aware that they have become more important geopolitically in recent years – a key reason why larger nations should take an interest in their defence development.

For European NATO allies and the European Union, Ireland’s current lack of significant defences is an area of vulnerability. This is especially true for the UK as Ireland’s closest neighbour. Russian warships and aircraft often loiter around the British Isles, especially around subsea cables, including in Irish territorial waters. While it is still very much a neutral country, if Ireland has the ability to effectively respond to such threats in its own territory and offer a deterrent, then the burden on the UK’s (and therefore NATO’s) stretched defences is lessened.

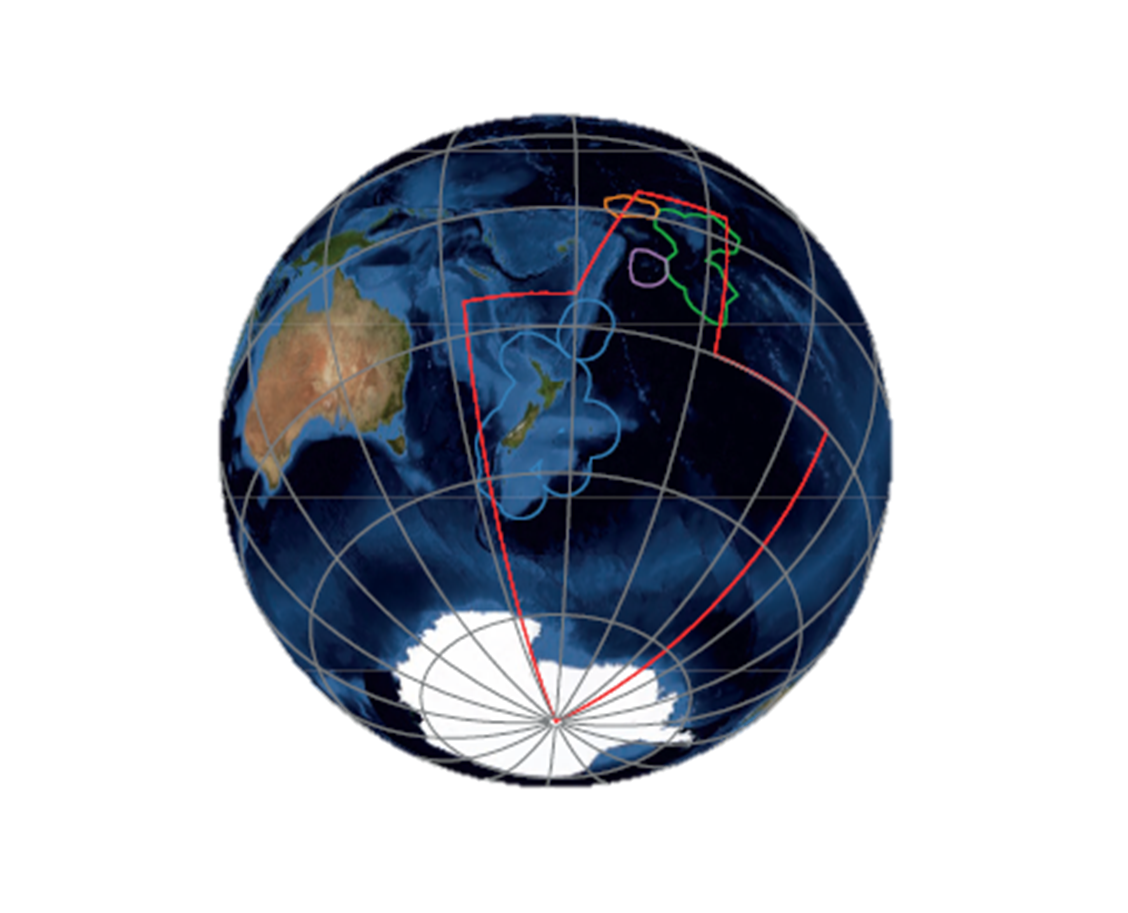

In the case of New Zealand, the United States’ fear of China’s growing influence and reach has made the island nation a far more important ally, both to the US and especially to Australia. Chinese warships are making longer-ranged patrols and demonstrative exercises between New Zealand and Australia, and New Zealand is also in a key strategic position to respond to issues in the South Pacific.10 A capable, long-ranged New Zealand Defence Force helps shore up this South-Eastern flank for allied Pacific nations, especially those concerned about Chinese activity. This is also very useful for Britain, especially noting the UK’s historic relations with many South Pacific nations – Fiji and Samoa especially, both of whom provide large numbers of soldiers for the British Army. While the UK can’t effectively respond quickly to problems in the region, New Zealand can. New Zealand’s role as a Five Eyes partner is also significant for intelligence-sharing in the wider Pacific region.

Conclusion

In an ideal world, neither New Zealand nor Ireland would need to build up their defences. Alas, reality is not ideal. The fact that these countries are no longer feeling as secure as they once did is indicative of the dangerous state of our age.

Other than looking at two nations that interested me, I wanted to use this piece to highlight the strategic importance of smaller states – not just Ireland and New Zealand, but also nations like the Baltics, Nordics, Singapore or the Arabian Gulf States. In my view, smaller states often have a much clearer sense of their geopolitical position and strategic requirements, unencumbered by the political and bureaucratic inertia that can affect larger countries - especially those with imperial legacies. Yes, on paper the forces often don’t look like much compared to the monstrous arsenals of larger countries, but they are often geopolitically vital for their location, economic and diplomatic heft, and agency. Ignoring these states and how they organise their defences would be a failure both of analysis and strategy.

Any thoughts on Irish or New Zealand defence? Do you think that other small states deserve their own deep dives? Let me know in the comments below.

All the best,

Matthew

The above two quotes come from the 2024 Irish Defence Policy Review and the New Zealand 2023 National Security Strategy respectively.

Ireland far more so than New Zealand.

The Siege of Jadotville is a solid war film based around Irish peacekeepers in the 60s, for those interested.

I am very aware of the complexities of determining the actual size of Ireland’s economy. Broadly GNI is seen as a better determinant than GDP, though definitely still imperfect.

Ireland has a ‘Triple Lock’ system, in which deployments can only occur if authorised by UN mandate, the government, and the Irish lower house (Dáil Éireann).

A point to note: the ANZUS treaty between New Zealand and the United States is partially suspended due to NZ’s long-standing adversion to anything nuclear. This is reflected in the official documentation which refers only to Australia in relation to ANZUS.

I’ve just recently visited Singapore so I have a lot of interest in the city-state. Be warned - more Singapore-related writing on the horizon!

However, both have strong tech sectors which could be boosted by involvement in defence.

For aircraft nerds, I’d suggest that the Eurofighter, Gripen, or the little Korean FA-50 would be likely options.

Also a reason why the French territory of Nouvelle-Calédonie is a key strategic position, and thus why France keeps a substantial military presence there.

Great piece. What's striking is how much cleaner their strategies are compared to the UK or US. No delusions of grandeur, just priorities grounded in geography, capability, and alliances.

Also worth watching: how both could become testbeds for dual-use tech adoption. Neither has the industrial inertia of a defense prime-heavy economy, which gives them more room to buy smart and integrate fast. That flexibility might turn out to be their biggest strength.

Good article Matthew. I undertook my Master’s thesis looking at Ireland’s self conception of neutrality particularly since the post-2022 Ukrainian conflict. The symbiotic relationship between neutrality and defence policy is starting to be slowly prized apart however it will be a long but necessary road for Irish policy makers. Overall NATO membership remains politically (and financially) unfeasible but Ireland is slowly appreciating the need for enhanced maritime and cyber protection as your article drew out.