The Defence of London

Protecting Singapore-on-Thames

Because we are breaking into the Summer holiday season, I thought I’d have some fun with this one. While the premise is fundamentally silly, hopefully it proves an interesting example of how military force structures should be designed.

After a bitter and acrimonious divorce, London has voted to secede from the United Kingdom and go its own way. The new city-state has many advantages – it is one of the world’s premier financial centres and a hub for global business, as well as having a reasonably large, well-educated population – but now has to contend with being completely surrounded by a sullen, hostile England.1

The fledgling nation must work out now how to safeguard its independence. How is London going to defend itself going forward? Let’s find out.

Geography

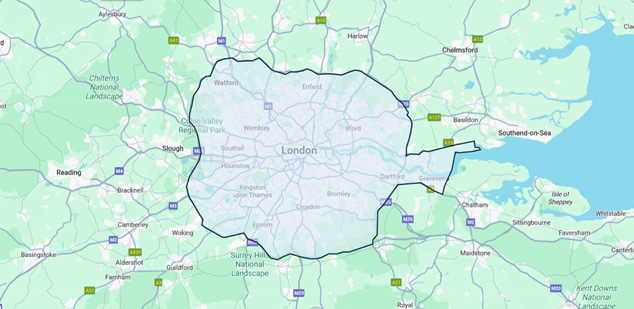

After much hard-fought negotiations, the borders of London were set at the M25 motorway. In addition, due to London’s critical need for access to ports further along the Thames, the old boroughs of Havering, and the two constituencies of Dartford and Gravesend north of the A2, are also now under London sovereignty.2

This provides the new state of London with a population of over 10 million, and a variable, if densely packed, geography: roughly 70x46km at its widest. Much of it, of course, is urban; however, London is far more verdant than one might think, thanks to the metropolitan green belt, and includes significant areas of countryside and farmland, especially in the South.3 The River Thames is obviously the standout geographical feature, cutting through the city west to east and providing it with its only route to the outside world, stopping London from being completely landlocked.

London does not have extensive military infrastructure, as historically most of the British Armed Forces were stationed outside the capital. There is a scattering of old Army bases and Reserve depots, including Wellington Barracks and Northwood Headquarters, but almost no training areas to speak of. In terms of airbases, RAF Northolt (as it was) remains within the M25, and there are a number of civilian airports and airfields that could be converted for military use. London no longer has any naval infrastructure other than the tiny HMS President, though there are extensive commercial ports that have military utility.

Strategic Concerns

London’s primary strategic concerns are that it is surrounded on almost all sides by an unfriendly nation, and that it is dependent on that nation for much of its food, power, and utilities. To cap it off, London has very little strategic depth – i.e. England is right on its doorstep and there is no buffer zone of land over which a hostile force might overstretch itself. England’s primary military encampments for its armoured force on Salisbury plain are only about two hours’ drive from the centre of London. Finally, London’s connection to the outside world is through the Thames Estuary: continued access to this waterway is critical and must be protected at all costs.

The beginnings of a Defence Strategy

London’s defence strategy would rest on three pillars. Firstly, a network of partnerships and alliances with other large states; secondly, the deterrent effect of a strong territorial defence; thirdly, the established ability to strike back and inflict significant damage on an adversary.

The first is to ensure that London is protected by association and alliance with other nations. Joining NATO (if it still exists in this timeline) is an obvious choice, though this might be blocked if England is still part of the Alliance. A strong relationship with Scotland might be on the cards if the northern nation also feels threatened by England, though that is contingent on inter-state relations on the newly fractured British Isles. Alternatively, cultivating strong relationships with major European nations – I imagine France and the Netherlands would be particularly strong bets – alongside the United States (unless it’s devolved into Civil War 2.0 in this timeline) would be vital for ensuring security. Finally, trying to cultivate England itself will be a major foreign policy objective, though this may be impossible depending on the state of both Londoner and English politics.

The second and third factors are mostly tied to force structure, which we will now look at in detail.

Broad Force Structure

London’s Defence Forces (LDF) would broadly fall into two separate joint task forces, each aligned to Pillars 2 and 3 of the defence strategy. The first would focus on the territorial defence of London itself – what I am going to call ‘Protection Command’ – and the second would focus on aggressively taking the fight to the adversary – ‘Retaliation Command’.

Noting London’s dense, predominantly-urban geography, Protection Command (‘ProCom’) would be focused heavily around maximising the advantage of interior lines and implementing operations of denial and classic urban defence to delay and degrade invading forces.4 ProCom would also control London’s airspace, with an emphasis on denying it to the enemy through multiple layers of both ground and air-based defences, and coordinate closely with civil protection organisations (e.g. the London Fire Brigade and Met Police) to ensure the safety of civilians and the continued running of basic services such as power, sewage, and healthcare. ProCom would also have to fight a significant cyber and informational battle to ensure connectivity and societal resilience remained strong. As an addition, ProCom would have the lead on countering hybrid and terrorist threats to London.

Retaliation Command (RetCom) would look more like a conventional western military force, focused on either regaining lost territory or enacting pre-emptive or punitive strikes on enemy soil. This would be a much smaller organisation but include heavier mechanised units for fast-moving offensives; special forces; surface-to-surface missiles; significant offensive cyber capabilities; and advanced fighter-bombers for deep-striking enemy territory.

London would always be outnumbered in any conventional campaign; therefore, the ability to mobilise quickly, and make use of force multipliers like strong organisation, good training, and effective technology would be key. A large reserve force that could be rapidly mobilised would be also required to counter the English advantage in manpower, whether through conscription or a strong volunteer reserve.

The Services

Now the overall Force Structure has been outlined, let’s look at the individual services of the LDF in some detail.

The London Army would be the largest service by far, and likely take the bulk of the defence budget. Divisions would be tailored to whether they were supporting ProCom or RetCom. ProCom forces would be heavily focused on light or lightly-mechanised infantry, artillery, and combat engineers. The latter in particular would be critical for constructing defences, barriers, clearing obstacles, and repairing fortifications and infrastructure.5 Unmanned aerial vehicles and unmanned ground vehicles would also be very useful for the style of urban-focused warfare that ProCom would have to wage. In addition, ProCom would require rear area security troops to assist the Metropolitan Police in countering the inevitable special forces incursions into the heart of London, alongside specialist enablers such as military police and CBRN.

RetCom forces would include heavy armour for counter-offensives to regain ground, or even to strike out towards vulnerable points in England, supported by effective long-range rocket artillery. There would also likely be a need for an elite commando capability, able to rapidly strike and raid English territory whether by land or river-based insertion.

The London Navy would be a much smaller force focused on keeping the Thames and the route to the North Sea open. I’d imagine a fleet of patrol craft, missile boats, unmanned surface vessels, minehunters, and perhaps one or two small corvettes would be appropriate.6 Most of these vessels would be under ProCom, other than a few that would be tooled to menacing English harbours or supporting RetCom’s raiding efforts and commando forces, perhaps with river-based naval gunfire support.

The London Air Defence Force (LADF) would include both aircraft and ground-based air defence units. ProCom LADF forces would be almost entirely focused on keeping London airspace clear of threats, employing sizeable numbers of ground-based air defence weapons, including counter-UAS and anti-ballistic missile defences.7 RetCom, by contrast, would wield long-ranged missile launchers of their own, fighter-bomber aircraft, attack helicopters, and lots of unmanned aerial vehicles for reconnaissance and strike. There may also be a number of transport helicopters for assisting with rapid re-deployment of forces around London, and support aircraft providing Aerial Early Warning (perhaps through loitering drones rather than something like the E7 Wedgetail).

As a relatively compact force, the LDF would likely place many of its enablers (medical, intelligence, etc) under an integrated joint command. This would also include information and cyber warfare units – defensive cyber would naturally fall under ProCom jurisdiction, while offensive cyber would be tied to RetCom.

A hypothetical war scenario

Imagine England tries to enact a coup de main and seize London terrain in order to gain leverage over the city-state. A key vulnerability for London is that much of its critical infrastructure is right on the border with England – in particular Heathrow Airport, Tilbury docks, and the crucial London Gateway port just west of Canvey Island. Thus, any English military incursion would attempt to take this vital ground as quickly as possible.

A hypothetical war scenario might see England’s initial attack focus on two major efforts – one an armoured thrust up from Tidworth towards Heathrow, and another a rapid advance on Havering and the London Gateway Port from Colchester, home of the Parachute Regiment. These two avenues of approach, by happenstance, also tend to be over the flattest terrain, so more favourable to manoeuvre forces. Other probing attacks might occur as feints, or to move to quickly encircle and isolate border towns like Watford or Dartford.8 At the same time the English Air Force would work hard to destroy its London counterpart of the ground, while the English Navy would look to close off the mouth of the Thames for shipping. English special forces and fifth-columnists would likely be wreaking havoc within the city, while cyber-attacks and information operations would be unleashed on the London population.

London, if its defence planners had any wits about them, would have put in major contingency plans for defending its critical infrastructure, including rapidly-deployable barriers and pre-prepared positions for quick reaction forces to inhabit.9 The aim of the initial defenders would be to hold off and delay the English long enough for the rest of ProCom forces to mobilise. At the same time, high-readiness elements of RetCom would prepare for initial significant counter-attacks, especially if English forces manage to capture substantial areas of key terrain.10

After the initial attack was blunted, London would itself go onto the offensive. RetCom, now fully-mobilised, would look to start pounding English military infrastructure with missiles, aircraft and cyber-attack. Armoured forces might strike out at lightly-held English towns in order to create dilemmas for the adversary, while the London Navy would try to break open the English blockade with minehunters and volleys of missiles, torpedoes, and drones – potentially even menacing key English ports like Felixstowe. Special Forces teams might infiltrate up the western Thames to cause havoc behind enemy lines. The strategic objective would be to place London in a position where its own defences were secure, but it also held some English territory, giving it diplomatic leverage in the inevitable negotiations leading to an end in hostilities. London’s forces are not set up for significant manoeuvre warfare at scale, so would likely halt once enough English territory has been secured for strategic advantage.

Conclusion

Much of the above was inspired by the defensive policies of Singapore and Israel (with a dollop of Taiwan and Finland), as two small countries with a hefty focus on defence – in comparison to the nations that I covered in my last article.

This, obviously, has all been a bit of fun, and allowed me to indulge my weakness for alternate history. However, hopefully it’s also highlighted how a military force should be designed for the strategic context it faces, and why there is no such thing as a ‘perfect’ military.

I leave you with this question – is the military of the UK, or that of your own country, well-designed for the strategic problems it faces? Discuss.

All the best,

Matthew

I surmise that in any London secession scenario, the United Kingdom would be breaking apart anyway – hence I will use the term ‘England’ thereon, as I imagine Scotland, Wales, and probably Northern Ireland would have left the Union.

Before anybody takes up arms against me – yes, I know this is much larger than Greater London. Yes, I know that the politics of outside constituencies joining London is hilariously unrealistic. I’m literally talking about the secession of the national capital here, let’s not get too excited about the ‘realism’…

Estimates suggest that 47% of Greater London is ‘green’, with 22% being part of the Metropolitan Green Belt.

Interior Lines: basically, London forces have shorter distances to travel than attackers and therefore can theoretically move more quickly to where they need to be. Type ‘Jomini’ into Google/Firefox/ChatGPT if you want to learn more.

It goes without saying that London would need to build up significant military and defensive infrastructure - bunkers, hardened aircraft hangers, and areas that civilians could safely congregate, including expanding the Underground’s availability as a massive air raid shelter.

The Navies of Sweden, Finland, and Israel are indicative.

I considered whether squadrons of light defensive fighters would be useful, but considering London’s size and limited runway capacity I decided against it. Happy to take alternative views in the comments!

Being able to control the Dartford Bridge/Tunnel would be of enormous benefit to the invading English Army, connecting its forces across the Thames.

Interesting examples of pre-positioned rapid road blocks can be seen in the Demilitarised Zone in Korea, as highlighted in this article.

A point to note: ProCom forces are obviously not incapable of localised tactical offensive action (otherwise they would be pretty useless), but RetCom is specifically trained and equipped for major planned offensives.

This is crying out for a wargame!

Great fun! Two points - I would argue for a Western border that makes more use of the River Thames as a natural barrier Staines to Reading, and I would definitely incorporate Windsor into London as it has basic fortifications, a well armed militia (Eton) and would be be a buffer zone, to protect Heathrow. Secondly, how did you actually learn of our secession plans? I'm worried there has been a security breach .......