Vulnerable Britain

Time is running out

What a time to be alive.

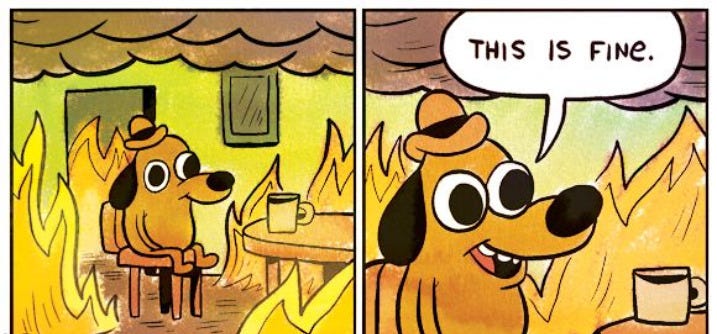

Everywhere one looks, the world seems unstable and on fire. This is especially true from a British perspective. There is still a major war being fought in Europe, our ‘closest ally’ spent the first half of January threatening to annex another ally’s sovereign territory, the Middle East is destabilising (again), there is a swathe of violence across Africa and parts of Asia, and China remains aggressive towards its neighbours and still utterly dominates critical supply chains. On top of that we have to deal with the long-term effects of climate change, demography and artificial intelligence, while experiencing significant domestic political disruption and being led by a government which seems adrift.

Have I missed anything?1

In such a veritable shitstorm, what is a middle power to do? This has been the conversation swirling around the policy circles and pundit class in London, though how much of the debate manages to penetrate the corridors of Whitehall is anyone’s guess. However, there is mercifully a growing consensus in policy circles that radical change is needed, not least in our security outlook and our dependence on America.

Recently I attended a live performance of the excellent Wargame podcast, in which former British politicians and officials play out the scenario of a Russian attack on the United Kingdom.2 When it first came out last year, the complete American refusal in the scenario to support us, even then, seemed a bit far-fetched.3 These days, post-Greenland, it does not. The United States is no longer the reliable ‘closest ally’ whose support we have enjoyed for decades, and the UK needs to start working out a new security arrangement that does not rely solely on American support.

Also, as an aside to my American readers. Some of you may have found the European reaction to the Greenland crisis to be overhyped. Please understand that when the world’s foremost military power threatens you, you tend to take it very seriously indeed. I had to personally consider the highly unlikely but no longer impossible scenario in which I might be remobilised in order to defend Europe against the military I had worked for only two years prior in Iraq, and with whom I had shared a bunker under fire. It becomes especially emotional when the US President dismisses the sacrifices made by European soldiers in the pursuit of American foreign policy objectives.

As such, there is a significant need in the UK to reduce our particularly extreme dependence on the United States for our security. This is going to be painful and expensive. As I have written about before, our defences rest on a bedrock of American support, technology and supply chains, all the way up to our nuclear deterrent. We can’t become completely independent, but the sheer scale of reliance on the United States is a huge risk, not least when US foreign policy priorities are not equal with our own. Even with a friendlier United States government, the American priority is going to be the Pacific over Europe - this has been blindingly obvious for over a decade to everyone, it seems, other than European policymakers. Understandably, the US are not going to prioritise giving us armaments and technical support if they are in a shooting war with the Chinese. In the worst-case scenario, the United States can make life exceptionally difficult for us if our strategic goals are seen in contradiction to theirs – this includes throttling the support for our nuclear deterrent.

What does this de-risking look like? Firstly, weaning ourselves off our addiction to American weaponry and equipment. This is as much cultural as anything else – we tend to love going for the most high-class weaponry (usually American) in all respects. For instance, while the F-35 is a very good warplane, I don’t think doubling down on buying more is going to help anyone, perhaps other than Lockheed Martin’s shareholders. More important than the weapons themselves is greater sovereignty in our intelligence collection and communications – while the UK has some significant strengths in these areas, we still rely too much on the vast quantities of data hoovered up and disseminated by the US. We need to avoid the default option of ‘partner with the Americans’ because it is easy, and start making hard choices about sovereignty and independence. We cannot be truly sovereign if we are structurally dependent on a single country for our entire defence apparatus.

Secondly, in my view, we need to continue deepening our ties with continental Europe, in terms of security, economics and political culture. Yes, the French are infuriating and the European Union is incompetent and heavy-footed, but they still share a common strategic problem and are our closest trading partners. The Northern JEF Nations, plus Poland, are like-minded on the threat and willing to act decisively; they really are our best friends, and we need to return the favour.

On a psychological note, we need to accept that we are Europeans and stop trying to play a silly game of latter-day ‘splendid isolationism’. We are no longer a world superpower with a global Empire. Times change and strategy changes with it. I’m extremely supportive of British efforts to remain an open trading nation and engage seriously with the Asia-Pacific, the Commonwealth and elsewhere. However, sheer facts of geography determine that we are Europeans first with European interests, especially when it comes to security, and we need to stop pretending that we are not. If the world is to splinter into rival protectionist power blocs, which looks likely, a European one is our most obvious home. To aid this, I think a little less obsession with American politics amongst our political class wouldn’t go amiss.4 Too many British politcos can tell you micro-details about gubernatorial elections in America but would blank on any facet of European politics or, frankly, any British politics outside the Westminster bubble.5

Finally, and most importantly, a sense of fucking urgency from the government wouldn’t go amiss. I truly believe that the current generation of senior politicians and officials, all brought up in a world where America was always available as the friendly big brother and war was something that happened ‘over there’, cannot psychologically or culturally compute the world in which we now exist. While there are some good noises coming out of the government – the new Armed Forces Bill promises some positive changes – the rate of change smacks of a peacetime mentality and is agonisingly slow. The fact that the Defence Investment Plan might be delayed until May is outrageous; two years into the government’s tenure and we are still no closer to tangibly improving our defences than before. The urgency of the moment requires us to take extraordinary measures and pump resources into defence now, not when ‘the fiscal situation allows’. As grim as it is to say it, there is a sizeable chance that Sir Keir Starmer, if he survives the next few months, may end up as a wartime Prime Minister, a possibility he seems utterly unable to comprehend. Even Chamberlain, of all people, seriously boosted rearmament in the late 1930s. Quibbling over percentage points of GDP and expecting to be patted on the back for making strident but empty speeches can no longer be the way forward. The best way to avoid war is to decisively rearm, and do so quickly.

I try not to be too negative on this website, but it is difficult to be cheerful at the moment. Despite containing many talented people and coming up with some genuinely good policy on certain issues, our current government is utterly unmoored, unable to force through anything despite an overwhelming majority in the Commons. Our domestic politics is taking a darker turn, dividing us and easily exploitable by our enemies. Despite the collective screaming from defence and foreign policy experts, the international threat isn’t taken seriously even as our European allies desperately pump money into their own defences.

The United Kingdom should be the keystone of Northern European security, the primary supporter of Ukraine and a beacon for tolerant, open liberal democracy. Our enemies should think twice about acting aggressively towards us and our allies. Instead, we seem adrift, unable to take painful decisions or improve our strategic position in a rapidly changing world. History will not thank our leaders for being timid at this moment.

Cracking Defence is a reader-supported publication. If you enjoy my work, please like, share, subscribe, and if you are able, buy me a coffee to support my work. All and any support is hugely appreciated.

Rhetorical question. Yes, there are a thousand other dramas that we could talk about.

If you haven’t already listened to it, you should.

The American side was played by popular Substacker Phillip O’Brien, for those interested.

There was a memorable article, which annoyingly I cannot find online, written a few years back by Janan Ganesh, in which he argued that Brexit could have only come about through a political class that was obsessed with America.

I honestly blame half of the UK’s political problems on this obsession with American politics.

"Finally, and most importantly, a sense of fucking urgency from the government wouldn’t go amiss."

Yes. My word yes 😬🤦🏻♂️😬🤦🏻♂️😬🤦🏻♂️😬

Yes, we had much regrets in Norway about WW2 that we did not seriously build up in 1930s. Analysis here tends to stress that we very well could have beaten back a German invasion had we invested more seriously in our defense when we saw what was happening on the continent.

Likewise there is urgency in re-armament now, and anyway that could be good for jobs. The urgency suggest it is worth borrowing money to surge the defense industry at this point.

And learning from Ukraine suggests we need broad preparation. Power plants must get secured. We ought to get more roof-top solar to have some power in case central power plants gets knocked out.

Bombing shelters need upgrades.

We must learn from Ukraine about distributed drone production. This is in a way a civilian skill. Learning how to use 3D printers and assemble drones should become part of school curriculum, or we need workshops and other things to spread the knowledge.

Ukraine is keeping their whole defense going in large part because of thousands of civilians in makeshift workshops assembling drones. They make millions of drones this way and they carry out 70-80 percent of battlefield casualties. This is not from traditional factories. This from the people.

We need this kind of full defense thinking.